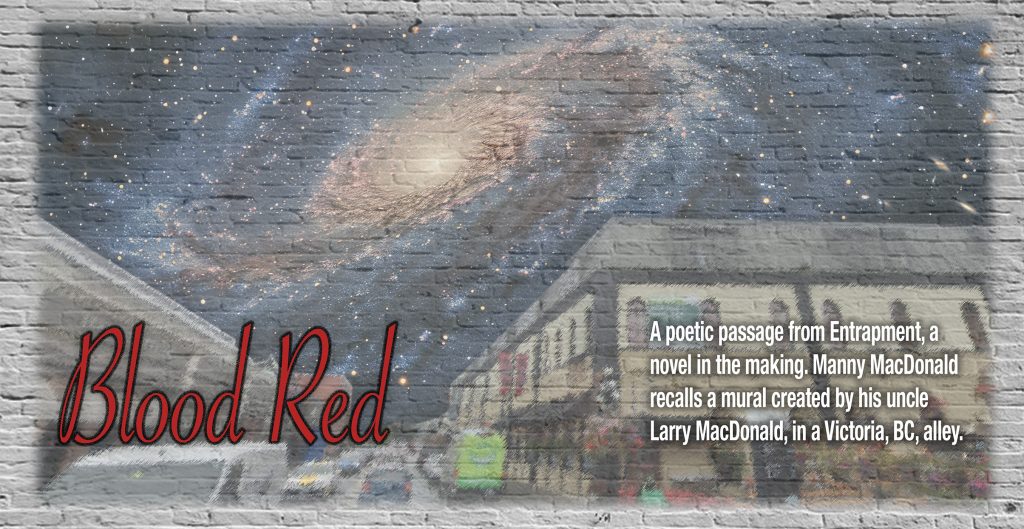

In this episode of Entrapment Lucinda and her son Manny visit her brother, who is creating a mural in a back alley in downtown Victoria, BC. Larry is living rough and homeless, and Lucinda hasn’t seen him for more than five years. Manny has never met his uncle. They are reconnected by Brenda Tanner, owner of the Inner Worlds Gallery and the back wall where Larry’s imagined world view is emerging stroke by stroke. Ten years on, Manny will compose a poem entitled Blood Red memorializing this encounter….

“Oh my god, aren’t you handsome?”

I liked Brenda Tanner the moment I met her. Liked her so much it felt sort of awkward because I didn’t have a right to feel so intimate so fast. She had stooped on her haunches to introduce herself to Manny, who was obviously thrilled to have a grownup—a beautiful, charming, cultured grownup—treat him like royalty. He giggled and beamed.

“Hi,” I said, interrupting their moment. “I’m Lucinda… Lucinda MacDonald.”

She took a moment to squeeze Manny’s shoulder, then stood up, turning toward me. Her delightfully startled, wide-open greeting took my breath away.

“Larry’s sister?” she asked.

I nodded, entranced by the musical timbre of her voice. Everything about her made me shiver with envy and joy. How can anyone be so beautiful, I wondered.

“I’m so glad you’ve come,” she touched my arm consolingly.

“It was the article in the Times Colonist. We’ve lost contact with him.”

“He’ll be pleased to see you, and…?” She glanced down at Manny.

“That’s his nephew, Manny,” I said. “They’ve never met.”

“Well, let’s set that straight. I was just closing up, so let me get my keys.”

“There’s a gate…”

“I know. I lock the parking lot up at night.” She explained that Larry got in and out via a back lane, wriggling through a narrow opening between a chainlink fence and his wall. “If he wasn’t so skinny, he could never do it.”

The remark nudged gently. How did Larry get so skinny? And how did he get so lost?

“Has he told you anything about his past? His family life?”

Brenda chuckled, “Larry’s not much of a talker. He speaks with his brush for the most part.”

“It’s a long story, a horror story. I’m not surprised he hasn’t put it into words.”

Rattling the gate open, Brenda ushered us into the parking lot. “He might be in his tent,” Brenda guessed, nodding toward a blue fabric dome at the far end of the lot. For a moment I felt like a mendicant approaching some sort of sanctifying shrine to do homage. I shrugged the thought off. “Larry?” Brenda coaxed as we approached. “You’ve got visitors.”

No response. The tent remained perfectly still, the hunched form of a frightened animal waiting to be attacked. “Larry,” she repeated softly, then gestured for me to say something, inclining her head toward the tent.

“Larry, it’s Lucinda. Please. I’d love to see you. We’ve missed you.”

For a moment, silence; then the rustling of fabric; then a relapse into silence.

“I’ve brought your nephew Manny with me. He’d like to meet you.”

More rustling; then a hand unzipped the tent’s flap; and Larry’s head popped out like a prairie dog’s. Squinting, he looked at Brenda, then me, then Manny, and smiled—a crooked, broken smile, but at least we had something to fix, something to work on.

I collapsed onto my knees and took his head in my hands. “I love you,” I whispered, trying my best not to cry. “Please let me love you!”

Manny edged up close to us. I couldn’t see him but felt his tiny presence, then his hand on my neck, and his other hand on Larry’s neck, and his cheek against my scalp. “And Manny loves you, too,” I smiled—the most pathetic, feeble smile I could summon, hoping that they could feel my joy as we huddled in our clumsy embrace, shipwrecked under a sea of sky.

Larry took us on a tour of his mural.

“He’s speaking!” Brenda whispered.

The words tumbled out of him awkwardly, as if he was an immigrant with a poor command of English. And his stuttering made him stall and start like a misfiring engine, but he was excited to be showing Manny his wall and pushed through his shyness and disability. “Th… th… thaaat’s Wharf Street,” he pointed to the centre of the scene. Victoria’s skyline, looking north, formed a jagged edge running the entire length of the parking lot.

The thought occurred to me that Manny could have walked up that imaginary road into the painting’s vanishing point about a third of the way up the wall.

“What’s there?” Manny pointed up at the white brickwork of the Inner Worlds gallery.

“Tha… tha… thaaat’s going to be the sky.”

“Wouldn’t all those bricks fall down and kill all those people in the street?” Manny giggled.

Larry laughed. Not the condescending laughter of an adult who knew better, but the conspiratorial hooting of a friend. “Well,” he said. “We just have to save the day, aaa.. aaa… and paint those bricks away. Poof! Gone!” He gestured grandly with a sweep of his arm. “We’ll make them into a black fabric sky, then poke some holes through it so people can see the starlight, then set it on fi… fi… fire at the end of Wharf Street with a blazing red ball of a sun.”

Manny scrunched his face into a mischievous frown. “But the sun’s over there,” he challenged, pointing west, over the rim of our brick-and-mortar-canyon toward the glare of the late afternoon sun. ‘And you can’t see stars in daytime.”

“Why,” Larry huffed. “I can put the sun anywhere I want. It can shine out anyone’s ar… ar… armpit…”

We all laughed at his teasing schtick.

“Aaa… aaa… as for the stars, only people with imaginations can see ‘em shining in broad daylight. People like you!” He pointed like a revivalist preacher issuing a godly commandment at my son, smirking at his own drama.

Never had I seen Manny look so pleased with himself. So proud!

“Tell you what,” Larry said. “When the time comes, I’ll get you to put a few stars in that black-velvet sky. Whaa… whaa… Whaddya think of that?”

“Yes!” Manny pumped his fist.

Brenda beamed, radiant as a gentle sun in our shadowed courtyard. I couldn’t help loving her, wanting her, but suppressed that secret desire, crushed it because I was afraid my love would destroy her, and me with her. I wasn’t even sure we could become friends but was prepared to put up with my yearning just so I could be close to her.

I’m haunted by that wondrous reunion with my brother. If things hadn’t ended the way they did, I might have let it settle in my subconscious, like a photo pressed between the pages of a family album. But things did come to an awful end, and that memory has become an inflaming spirit, burning through me like the blood-red sun that spills its molten light down Wharf Street in Larry’s mural. Ten years on, Manny memorialized that painting in a poem.

Blood Red

I’m walking down the avenue

In the middle of my day,

Thinking nothing’s old; nothing’s new

Which means I’ve lost my way.

Don’t know where I’m going

Don’t know what’s worth knowing

There’s no such thing as growing,

Everything stays the same.

People come; people go

We laugh, we drink, we clap, we cheer

Stand loud ovations to end our shows,

Though nothing’s changed, and nothing’s clear

We can’t know where we’re going

And there’s not a thing worth knowing

And there’s no such thing as growing

In this for-ever-saken here.

I imagined once a blood-red ball,

A blistering nova casting rays

Erupting atop a star-lit wall

Exploding my day-today.

I’d forgotten where I’m going,

Had lost what once was knowing,

Was shrunken, inward-growing,

In a world become deranged.