“I assure you, I am not given to spiritual fervour or joyous outbursts of any kind. My worship inclines to the thoughtful, quiet, even solemn—I hate drawing attention to myself or being in the midst of enraptured cultists.”

The Window Maker

“Bye. Take care of yourselves.” Noreen texted.

“You’re going to get fined for distracted driving, Dad,” Karl groused.

I suppose that was as close to an apology as I could have expected from her, Noreen not being a known connoisseur of fresh crow. The word ‘bitch’ presented itself, but I banished it and focused on the road ahead. Karl slumped within the traces of his seatbelt, like a man who’s given up wrestling against the bindings of a straight jacket. A reproachful urge gnawed my innards, the trapped rat of our relationship desperate to get out. I muttered an expletive and drove on.

“She ruins everything,” Karl complained.

Swinging left off Cypress, I accelerated east on Broadway. I could have agreed with him, I suppose. In retrospect, that might have been the thing to do. Form a bond of collusion, making Noreen the lightening rod of our bitter angst. After all, she truly had become a bitch and had earned the epithet in a thousand little snarky ways, which coalesced into a presentiment of infidelity, a predisposition to judgment.

Not that I cared.

Noreen was a smart-looking woman. She still turned heads, most of them grey, belonging to retirement-aged fellows with a penchant for unattainable ‘mature women’. It wasn’t so much her beauty that attracted the geezers in the crowd as that elegant assurance she radiated—that quality you can’t really sum up in a single word, unless it be élan. The thought occurred to me frequently that she still had a chance; she could start over if she left me, build a new life split between Kits and frequent vacations to Mexico with someone who would agree to go there and bake in the equatorial sun like a white-skinned potato.

“Jeez, Dad, watch out!”

The light at Cambie had turned red just before I entered the intersection. A guy trying to make a left turn from the opposite lane honked and glared. I drove on as if his rage was a species beneath my dignity, glanced in the rear-view mirror to make sure he hadn’t pulled a screeching u-ie, bent on chasing me down, smashing my windscreen, hammering the hood of my car with a crowbar, that sort of thing. He rocketed through the intersection, up Cambie, into the oblivion of past irritants and concerns, the flotsam and jetsam clogging my stream of conscience.

Once we merged onto Highway 1, we’d have clear sailing, I figured. I wouldn’t have to worry about testosterone-soaked maniacs racing up Cambie, lurching left onto 10th, left again onto Quebec, then cutting me off to exact their pickled-brain, TV-stoked vengeance. Everything would be okay. I breathed deeply, exhaled the noxious fumes of daily living, inhaled the sweet breath of an imagined Nirvana, and felt consciousness swell inside my head like a pink balloon that might have been lighter than air. I allowed it to tug gently against the constraints of flesh and bone—my here and now.

“I don’t know why I have to come on this stupid expedition,” Karl cut in.

“Your mother needs a break.”

“She could take one without packing me off to the boonies. All she has to do is leave me alone, just shut my bedroom door, and get on with her life. We’d both be okay.”

“We’ve been through all this,” I sighed.

Truth was, I’d wanted Karl to stay at home too. “I need a couple of days to complete my research,” I’d argued. “Just a couple of days, then I can start writing.”

“And I need a couple of days with you two out of my hair!” she snapped. “I need a break, some time to think.”

“About?”

“Some kind of fucking future that works!” she shouted and stormed out of the kitchen.

And that was that. For the next week, up until my departure, we played the avoidance game. Noreen kept busy at work, out showing houses, closing deals, and making money; I spent more time in my office den, or ‘out for a walk’, or at the library doing research. ‘Family time’ became a matter of tactics—asking someone to pass the peas in a tone that wouldn’t trigger an argument.

“You two need to go and see someone,” Karl interrupted.

Suddenly, the road was all that mattered. I longed to be out on the highway, out of the cramped city traffic, and onto a curving stretch of road where the engine could throb and the tires hum. I wanted to feel acceleration, the defiant lurch of a tight turn, motion with no purpose beyond the vanishing point of a driver’s concentration. Wanted Karl’s voice to be outside the focus of what truly mattered, and Noreen’s memory narrowed down to a disappearing point of light, like the signal of an old-time TV tube when you switched it off.

“I need to see the real you Karl,” I said, in spite of myself. “That’s who I need to see.”

That shut him up.

On the Cariboo Trail

I don’t know if Christopher actually read back issues of the Cariboo Sentinel to familiarize himself with the history of the place he had arrived at. But it’s something he might have done, I thought, imagining myself a newly minted and posted priest of the Anglican caste, arriving in the instant town I was supposed to bring to God. So, I scanned every available issue of the Sentinel up to and beyond his arrival and departure, trying always to align myself with Christopher’s point of view.

In the January 22, 1871 edition, he would have read the following item under the headline…

Mark Twain’s mining reminiscences

It was in Sacramento Valley that a deal of the most lucrative of the early gold mining was done, and you may still see, in places, its grassy slopes and levels torn and guttered and disfigured by the avaricious spoilers of fifteen and twenty years ago. You may see such disfigurements far and wide over California—and in some such places where only meadows and forests are visible; not a living creature, not a house, not a stick or stone, or remnant of ruin, and not a sound, not even a whisper to disturb the Sabbath stillness— you will find it hard to believe that there stood at one time a wildly, fiercely-flourishing little city of two thousand or three thousand souls, with its newspaper, fire company, brass band, volunteer militia, bank, hotels, noisy Fourth of July processions and speeches, gambling halls crammed with tobacco smoke, profanity, and rough-bearded men of all nations and colors, with tables heaped with glittering gold dust sufficient for the revenues of a German principality; streets crowded and rife with business; town lots worth $400 a front foot; labor, laughter, music, dancing, swearing, fighting, shooting, stabbing, a bloody inquest and a man for breakfast every morning; everything that goes to make life happy and desirable; all the appointments and appurtenances of a thriving and prosperous and promising young city – and now nothing is left but a lifeless, homeless solitude.

The men are gone, the houses have vanished, and even the name of the place is forgotten. In no other land do the towns so absolutely die and disappear as in the old mining regions of California…

Lest you feel angry at the desecration and sorry for the demise of its perpetrators, however, Twain quickly shifts into what appears to modern eyes a sort of preposterous eulogizing of lust, greed, and violence…

It was a driving, vigorous, restless population in those days. It was a curious population. It was the only population of the kind that the world has seen gathered together, and it is not likely that the world will ever see its like again. For, mark you, it was an assemblage of 200,000 young men, not simpering, dainty, kid-gloved weaklings, but stalwart, muscular, dauntless young braves, full of push and energy, and royally endowed with every attribute that does to make up a peerless and magnificent manhood—the very pick and choice of the world’s glorious ones. No women, no children, no gray and stooping veterans—none but the erect, bright-eyed, quick-moving, strong-handed young giants—the strangest population, the finest population, the most gallant host that ever trooped down the startling solitudes of an unpeopled land.

And where are they now? Scattered to the ends of the earth, or prematurely aged and decrepit; or shot or stabbed in street affrays; or dead of disappointed hopes and broken hearts; all gone or nearly all; victims devoted upon the alter of the golden calf; the noblest holocaust that ever wafted its sacrificial incense heavenward. California has much to answer for in this destruction of the flower of the world’s young chivalry.

It was a splendid population, for all the sleepy, sluggish-brained sloths stayed at home—you never find that sort of people among pioneers; you cannot build pioneers out of that sort of material. It was that population that gave California a name for getting up astounding enterprises and rushing them through with a magnificent dash and daring, and a princely recklessness of cost or consequences, which she bears to this day—and when she projects a new astonisher, the grave world smiles and admires as usual, and says, “Well, that is California all over.”

I suppose Sentinel Publisher Robert Holloway printed that as a thought-provoking comparison between the boisterous unfolding of history in the gold mining communities of the Cariboo and California. But I find it hard to believe his readers didn’t see a disturbing prognostication in the item, in its strange mixture of eulogy for the rough and tumble 49ers and its descriptions of the despoliation they had wrought and the utter desolation and ruin—oblivion, actually—their towns had fallen into. How could a man of Christopher’s intelligence fail to see the vanishing point of history in that item? The Sentinel itself would go out of business by 1875.

The first report about Christopher Newman I found on its pages appeared in a brief, printed on July 5, 1871:

Barnard’s Express, with mails, arrived at 6 o’clock last evening, bringing the Eastern and Canadian mail, and the following passengers: Mr. Gurham, J. Wadleigh, from Yale; Mr. and Mrs. Parker and Mrs. Michaels from Last Chance; and the Reverend Christopher Newman from Victoria, who was met by a delegation from his congregation. From all accounts, there will be more to tell about the Reverend Newman.

There would indeed be many more Sentinel references to the Rev. Newman. Holloway latched onto Christopher’s story the moment the ‘renegade’ priest arrived in town. I’m not sure if the newspaperman liked or disliked his tormented subject—my guess is he’d simply got hold of a good story, which would boost subscriptions—but he delighted in printing every titillating tidbit of the ‘good reverend’s affairs,’ as he put it. His—I won’t say ‘jaundiced’—prose form a haphazard and distorted chronology of my great-great-grandfather’s and mother’s histories during the time they met and fell in love.

It’s too sparse and skewed a record to really piece together the events of their lives, though, or the overpowering grip of a passion that drew them inexorably into orbit. They were not important enough to have extensive third-party sources available for research. Like most people throughout the ages, the memory of them simply faded, an echo weakening exponentially generation after generation, absorbed in the architecture of history. So I’ve intermingled fact with speculation, completing the story that opened for me with the reading of my great-great-grandparents’ letters.

After all, available facts rarely amount to anything that approximates truth; it’s only when we connect things in our imagination that we discern the possible meanings of history. Imagination, and in this case, a phenomenon—call it psychotic or psychic—that warped the flow of time for me, intermingling present and past. Is it possible to imagine something so fervently that it actually becomes real? Something you can hear, see, reach out for, and touch? I’ll leave that for you to decide.

Suspension Bridge

Karl and I followed family tradition, stopping at the Home Restaurant in Hope for a late ‘greasy spoon’ breakfast. We hadn’t talked much, not at all since I’d deviated from our familiar route to Hope via the Trans-Canada Highway. I’d decided to take the Lougheed route instead, on the north side of the Fraser. It offers more evocative views of the river and would take us across the mouth of the Harrison, one of the original routes up to the Cariboo. Karl objected to the detour, then pretended to sleep the rest of the way to Hope; I pretended to believe he was sleeping; we both felt the pressure of silence building inside the passenger compartment of the hurtling car.

“Why so glum?” I asked after we’d ordered our food.

“I don’t want to be here, Dad!”

There are different modes of decay: corrosion, which gnaws at the innards of things, gradually rendering them dysfunctional; disintegration, when things fly apart, the tensile strength no longer able to overcome the centripetal force of our torqued lives; collapse, when our inner logic no longer holds and suddenly gives way. I sat opposite Karl in our booth amid the animated buzz of the Home Restaurant, wondering what version of ‘going wrong’ was pulling our family apart?

“Will there even be a Wi-Fi signal at this place we’re going?”

“Can’t you survive offline even for a few days?”

We went back to masticating our scrambled eggs, waffles, and hash browns after that. I’d framed my retort as sympathetically as I could, adopting the pleading tone of a desperate dad. It still came across as criticism, and Karl went sullen on me again. We finished our breakfasts, then headed out in silence.

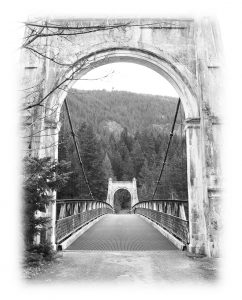

About 30 minutes up the road from Hope, you pass through Alexandra Bridge Provincial Park. We stopped to take a look, following a remnant of the original Cariboo Wagon Road down from Highway 1, through a mixed forest of Douglas fir, maple, and birch trees, flanked by mossy granite outcroppings. Our boots crunched on the stretches of gravel and crumbling pavement that lead to the bridge, which dates from 1926. It replaced the original suspension bridge, built in 1863, which was washed away by floodwaters. I’d managed to cajole Karl out of the car, but he griped the whole way down about how ’dumb’ it was, hiking to a “stupid suspension bridge in the middle of nowhere on a road that doesn’t go anywhere anymore.”

In fairness, the whole exercise was of questionable sanity, let alone value. My father died; that allowed my mother to carry out the posthumous instructions of my great-great-grandparents concerning the passing on of an old tobacco tin and its revelatory journals, and here I was frog-marching my griping son down a disused trail to a rusting monument of a bygone era. What could Anna Armstrong and Christopher Newman possibly have to do with me? With us? With the 21st century?

Time flows like a river; it doesn’t judder like the flickering images on a movie screen. It’s seamless. Memories live in the here-and-now, not as fragments of some distant past.

“Huh?”

I stopped and looked around to see if this voice I heard was accompanied by some kind of apparition. Fear seeped into me, a tingling sensation like dampness penetrating skin, chills shooting up and down my spine, shivering the neural network. The forest whispered assuringly, unperturbed. Karl glanced back, as if I’d been addressing him, then grumbled and pushed on, eager to get our side trip over with. Mind blip, I told myself. An embarrassing episode of mental incontinence, which I would make sure never happened again, clenching my mind shut against the possibility.

Gravity drew us on, down the snaking path that had once been the main route between Yale and Barkerville, down this capillary end of the industrialized world’s superseded highways. You can see the Alexandra Suspension Bridge from its modern-day successor, a typical wonder of 20th-century engineering, vaulting the muddy, boiling waters of the unnavigable Fraser. It connects Victoria to St. Johns via the ballyhooed Trans-Canada Highway, successor to the Canadian National Railway, successor to the brigade and canoe routes, all of them testaments to human ingenuity, lust, invasiveness, and greed.

“The Stó:lō people have been here for ten thousand years,” I said.

“Yeah?” Karl marvelled with as much enthusiasm as a poked corpse.

Time first travels on paws; even now, it begins its journeys on bare feet, connected to the land and what the Sto:lo people call its Xexá:ls.

“They hunted, foraged, and fished in this territory for thousands of years before Simon Fraser showed up.” I ignored the interruption, hurrying through my narration, cranking my voice up a notch. “They had told their own creation story for millennia before your great-great-great-grandfather arrived with his Bible and robes.”

“Uh-huh.”

We rounded a turn, and the approaches to the Alexandra Bridge came into view, its forlorn grandeur—dedicated to a long-since dead and forgotten princess—still stubbornly resisting the implacable surge of nature, the forests encroaching from every side, the river dashing against its stolid piers.

“Wow!” I said. Karl looked bored.

The first bridge wasn’t so grand.

“Pardon?”

“I didn’t say anything,” Karl protested, looking annoyed.

“No-no,” I apologized. “I wasn’t talking to you, son.”

He stared… Pointedly.

“I was talking to myself. This place, it has a voice,” I pleaded.

“Sure, Dad,” he said, sauntering on ahead, out onto the metal grating of the bridge deck.

I only crossed the predecessor to this bridge twice, the first time heading up to Barkerville; the second, back down in pursuit of my Anna.

This is crazy. Who are you? I demanded, as if I didn’t know.

Light-headed and dizzy, I made my way over to the bridge’s rail, looking down from its concatenation of girders, nuts, and bolts at the roiling river below, then up at the orange span of the new Alexandra Bridge, which arched the Fraser like a gigantic metal bow.

You’ve been searching for me, and here I am, your long-lost ancestor.

I’ve been researching; there is a difference.

I should have thought you’d be happy. Elated, actually.

To be having a conversation with something I don’t believe in—something that can only indicate some kind of psychosis?

Ha, ha! The funny thing is—the superb irony, I suppose—I don’t believe in me either, or you, for that matter. So, we’re in agreement there, and might as well be agreeable in our mutual astonishment.

“What!” I scoffed. “You! Deny me!”

Then, remembering myself, I looked about to make sure Karl hadn’t overheard us.

Oh, get over it, man! Do you want to know my story or not? I can assure you that part of our conversation will be real—the historical aspect, I mean, the continuation of my and Anna’s journals.

I hesitated, not so sure now that I wanted Christopher Newman’s voice to be gone.

The coach I was taking up stopped here en route to Barkerville. A mule train was coming down the other way, and we had to wait for its passage. I can still hear the clatter of hooves, the rattling of harnesses and traces, and the chuffing of the beasts. I had disembarked from the Barnard’s Express and strolled out onto the bridge after asking the driver to catch me up on the other side. I wanted to be in this place—to experience the whispering of needles and leaves, the buzz of insects, and the incorrigible gush of the river becoming part of me, interpenetrating the spiritual essence I had come to believe in. The heat was oppressive; my cleric’s collar chafed. I wanted to rip it off, and my jacket too, shucking the ridiculous effrontery of respectability and authority in this wilderness that was to be my parish.

Christopher laughed. Funny, I’ve come to appreciate the indistinguishable difference between the words ‘parish’, as in the jurisdiction of a priest, and ‘perish’, as in going down with your ship. ‘Homophones’ I believe such pairings are called. Of course ‘synonyms are words that sound different but have a related meaning… Like Christopher Newman and Kyle Welland, perhaps? Is it possible the spirits of you and I are one and the same in many aspects? That we share a common origin and purpose?

But enough with word play. Shall I come again. Haunt your thoughts and dreams?

I felt my head nod in agreement, like a bauble head mounted on a spring, sensitive to the slightest motion—unable to resist, even though I might have been on the tipping point into madness.

Arrival

The Wells Inn is a charming mashup of what looks like Tudor and Spanish influences, flanked on one side by a ‘deluxe junk’ shop, on the other by an old foundation, long since abandoned and concealed by a weather-worn fence. The surrounding town has an aura of defiance about it, with the hotel perhaps being the cornerstone of resistance to decay. Many of the village’s buildings and homes are brightly painted—blue, red, mustard, all sorts of cheerful colours—as if to proclaim a setting vibrant as any street in Bogota, or Cape Town, or St. John’s. But the stalwart good cheer is contrasted by evidence of dilapidation: empty lots, businesses with ‘building for sale’ signs affixed to them, facades curling or worn away by the relentless scrape and rub of time. It’s a place that appeals to a certain frame of mind.

I’d opted for the extravagance of separate rooms. Karl and I would still have plenty of father-son time, but I also wanted a space where I could be alone and escape the withering commentary of a young anarchist whose bitter ennui with the world didn’t exclude me and Noreen. It was, in fact, directed at the two of us. I had to preserve at least a modicum of my original intention in coming to Barkerville—stake out a refuge where I could be alone with the ghosts of Anna Armstrong and Christopher Newman! My having met Christopher that morning, in person, so to speak, only confirmed me in this hope. I needed a place where I could mind-talk freely if he materialized again. Where it would be okay to lapse into… what could I call it? Fantasy?

“We’ll spend tomorrow in Barkerville,” I said, over dinner in the hotel’s Pooley Street Café. “On Wednesday, I’ll be doing some research and writing. You can drop me off at Barkerville, then take the car. Go do some exploring. Maybe check out Quesnel?”

“Oh! That’ll be fun!”

“It’ll get you out, son!” I pleaded. “Away from that god-damned computer, into the real world.”

“This isn’t the real world, in case you hadn’t noticed, and I’m not going to find it in Quesnel, either.”

I clamped my jaw shut.

You shouldn’t let him speak to you like that.

Shut the fuck up!

Oh! Charming! Surely you can respond in a more intelligent manner!

He’s upset, dear. Let him be.

Anna? I said.

“Dad?” Karl was staring at me, waving from the other side of the table. “You okay?”

I took a gulp of water and swallowed hard, trying to dampen the critical massing of my emotions: I bristled at Anna’s brusqueness on the one hand; was confused by Karl’s anxiousness on the other. I’d struck a nerve with my mental lapse. He really does care for me. Deep down.

Don’t get your hopes up. The injunction sprouted like a weed on steroids. “I’m fine, son. Just thinking, that’s all. What about you?”

“Okay, too. Except I don’t like your plan.”

“Oh?”

“I’m not going to spend all day tomorrow drifting around a ghost town. I’m not into it.”

I concealed the sting of disappointment, even as I chided myself for the upwelling of relief that accompanied it, doing my best to look bright-eyed and interested. “What will you do, then?”

He shrugged.

“Please, Karl, tell me you’re not going to sit around the hotel room all day, playing video games.”

“Okay, I won’t tell you, Dad,” he smirked.

“Seriously, Karl, you’ve got to get out, take some chances, piss a few people off, and I don’t mean cartoon characters in a video game.”

“I piss you and Mom off, don’t I?”

“Touché, but you know what I mean, son.”

“Yeah, I think,” he said. “But do you know what you mean, Dad? I mean, really know?”

His challenge puzzled me. “Look,” I sighed. “I love you, Karl. Mom loves you. But you’ve got to take some risks, right? Nothing significant happens in your life unless you put your beliefs on the line, son. I’m not talking about the stupid chances young people take, mostly young men; I’m talking about believing in something, and going for it, and staking the hard work and personal commitment it takes to make your vision real.”

“And if I don’t have a vision?”

“Then look for one,” I urged, my voice constricted by desperation, like steam blowing out the check valve of a pressure cooker. “All the stuff we have, the consumer crap, it’s all designed to distract us, Karl, to make us feel we’re fulfilling our lives by buying nice shiny things: big houses, flashy cars, boats, jewellery, big screen TVs… it’s the new opiate of the masses. And video games! Well, they’re the ultimate pacifier, son. Millions of kids are hooked on them, and they stay hooked even as adults. You’re being manipulated, don’t you see? Just like a salmon attracted to a flasher and a wiggly lure, you’re being played.”

“Uh-huh,” he said.

Drop off

Next morning, Karl dropped me off at the Barkerville visitors’ centre. “Bye. See you at six,” I said, trying hard to infuse the moment with a bit of good humour. The car bucked forward as the door slammed, and Karl careened out of the parking lot. I watched his profile through the driver’s-side window, a feeling of helplessness asserting itself as he sped out of sight. There had been an aura of intensity about him that morning, which disturbed me. It seemed he’d made up his mind about something, but I had no idea what.

I sighed, turned, and trudged off in the direction of the Barkerville reception centre to pay my way in.

By mid-day, the streets of the town would be teeming with tourists, buskers in period costume, horse-drawn carriages, and such. But it was just after opening, and things weren’t in full swing. I made my way up the main street toward the Barnard’s Express office. That’s where Christopher would have disembarked, just a short distance from St. Saviour’s, which he would have seen for the first time on his way into Barkerville. I imagined myself in his place, suddenly rattling up a pioneer thoroughfare after having traversed miles of wilderness. How shocked and amazed I might have been at this tenacious, bustling community—how it had laid hold of the valley like a rash. Or an anthill, its busy citizens plundering the surrounding landscape, sluicing off its water, gouging its soil, hacking down its trees—all for the sake of some shiny metal that, really, had little value other than its lustre.

I was fascinated and appalled.

“And yet, you wanted to be here,” I challenged.

Not quite. I wanted to be out from under the whole superstructure of religion. Until that very moment, I had not seen my posting to Barkerville as any kind of banishment, even though I knew that’s how it was supposed to be seen. That Bishop Hills had been informed of my rebelliousness and instructed as to how I should be treated was quite clear from the outset and didn’t come as a surprise. He was a staunch Anglican, was Bishop Hills, one of the rivets, I dare say, stapling the high church together. For him and the old guard at home, my transportation to Barkerville was no doubt seen as a consequence, if not a punishment, for my obstinacy—perhaps apostasy would be a better word. I won’t say I wasn’t dismayed by that first sight of my parish. Any romantic notions I had entertained about being a wilderness priest were as mangled and blasted as the surrounding landscape. But I rallied as we pulled up to the express office, managing to put on a good face as I stepped out of the carriage into the midst of the little greeting party that had been assembled on my behalf.

I imagined Christopher facing the Barnard’s Express office, the reception coterie gathered on the boardwalk, nervously awaiting the arrival of God’s representative on their earthly frontier. Were they excited? Nervous? Both? Were they prepared, in a metaphorical sense, to throw their jackets on the ground before him? Lay down branches of spruce and fir to carpet his way?

Pooh! It was nothing so grand as that. The group consisted of: Mr. and Mrs. Wilmot, the hardware merchant and his wife—they both sat on the board of St. Saviour’s; that scoundrel of a newspaper man, Robert Holloway, who never took a note in his life because he made everything up anyway; the school teacher, Frances Whitmore; and a photographer, whose name I cannot remember and whose pictures I never saw.

“Louis Blanc?” I suggested.

Yes. That’s the fellow.

“Welcome to Barkerville, Reverend Newman!” Wilmot said, shaking my hand as if he were trying to dislodge berries from a bush. I thanked him, and he stepped aside so I could meet the others. Mrs. Wilmot actually curtsied, but in a stiff, unyielding way, which suggested an edge of resentment. I thought instantly, ‘There’s trouble!’ She seemed a stern, rigid woman, the type I would judge low church rather than high—she had that evangelical smugness about her. I was still chastising myself for that unfavourable impression as I took Frances’ hand, which nestled in my own as softly as a captured dove. She bobbed; my heart actually skipped a beat, and I said, “How do you do, my dear?” in a fatherly tone, even though she was no younger than me, which made the expression wholly inappropriate. I blushed. I could feel Mrs. Wilmot’s eyes on the two of us and knew that I was not the only one in the group being judged harshly. “Very well,” Miss Whitmore said, smiling brightly. Holloway, too, was observing the introductions shrewdly, I thought. We nodded, seeming to have mutually agreed that no other greeting was needed between the two of us.

“Shall we go to our house? We have assembled a few parishioners to greet you, Reverend,” Wilmot said, cutting short the formalities.

“I hope they won’t mind waiting a few minutes more, Mr. Wilmot,” I countered. “I would very much like to see St. Saviour’s from the inside.” He looked startled for a moment, then glanced at his wife and back at me. “Of course!” he said. “Of course!” and off we marched, from the Barnard’s Express office, and down the road to St. Saviour’s, me at the head of our little band.

There’s something ridiculously grand about St. Saviour’s. Its ‘carpenter gothic’ design can’t support anything so sublime as the haughty title ‘architecture’ bestows; you need vaulted stone for that. Its interior doesn’t reverberate the same way a true cathedral does, amplifying the human voice to a godly resonance that seems to boom at you from every direction. St. Saviour’s organ squeaks and groans, accompanying the gaggle of mismatched, off-key voices in a church choir too small to mask its deficiencies with sheer power. These rustic noises leak out through St. Saviour’s seams and cracks, giving the impression that instead of a house of god, the place might be a factory for skinning cats. You need something obdurate, bound together by mortar and steel, to achieve the resounding thunder of a cathedral. And yet, this doughty little building at the foot of the town’s main street has a sanctity all its own.

I rejoiced at the sight of it. Lord, how elated I was to be pastor of this picturesque little shrine—not so much a church as a barn, really, stretched heavenward in its simple design. As we approached, I laughed, for it occurred to me that the front of this tiny cathedral could be construed as a face, with its window-eyes peeping up at the sky and its entrance mouth shaped to sing hosannas that would spill out onto the street.

“Do you find our church worthy of laughter?” Mrs. Wilmot asked.

“Christ was born in a stable,” I replied. “I should like to think the whole universe laughed in chorus at that glorious moment. It’s unbecoming, I think, to always be dour and pompous in our praise of the Lord.”

Miss Whitmore raised her eyebrows at my retort, and we exchanged a smile.

Wilmot fumbled with some keys, unlocked the front door, then stood aside. I believe he was intending to gesture me in but thought better of it, simply moving out of the way instead to let me by. Nave, chancel, pulpit, alter—all the divisions of a proper church were there, of course, but crowded together in so compact a space as to make distinctions between one function and another entirely superfluous. I made my way up the aisle, conscious of the little procession we made, our footsteps clattering on the floorboards. Light poured in at the chancel windows, and I was drawn toward it, floating, as it were, in the direction of the alter. I raised my arms and welcomed that purifying energy—begged it to burn off anything unworthy in me. For a minute or more, I stood like that, aware that the others were becoming uneasy and impatient.

“They will never believe the truth.”

This conviction came to me not so much as a thought as a voice manifesting within the cathedral of consciousness—a pronouncement I might disagree with but could not avoid. It had been formulating for many years, long before I’d decided to become a priest, before I’d even been born. It had only been waiting for me to hear it—to believe it.

Gone Missing

Karl wasn’t at the townsite entrance when I went to meet him. I waited around for half an hour, then set off on foot, angry. One thing! Just one thing! That’s all my wayward son had to remember. And he’d forgotten, or fallen asleep, or got caught up in one of his effing video games. There was no cell signal in the area, so, short of going to the visitor’s centre and explaining my situation, then asking to use the phone, I couldn’t reach him. I decided to walk the six kilometres to Wells instead. Walk and think. The heat of the day was dissipating, but still, it wasn’t long before a film of sweat seeped out of me. I could feel it gleaming on my forehead, making my shirt stick to my back, contributing to my sense of frustration—of stewing in my own juices.

There’s a spur off the Barkerville Highway called Reduction Road. I’d noted it on Google Maps when I was checking out the Wells-Barkerville area. I even explored it in Street View, getting acquainted with the local topography. I decided to go that route. “It’ll serve him right,” I thought. Karl might drive by on Route 26, discover I wasn’t at the Barkerville visitor’s centre, where I was supposed to meet him, and wonder where I could have gotten to and why he hadn’t passed me on the main road.

Maybe he’ll worry. “Yeah, right!”

A grasshopper snapped its wings, launching itself into erratic flight; crickets chirped; their companionship made me feel more alone than ever. What was I to them? A vibration, a chemical tang in the atmosphere, a passing shadow? They cannot know what I am; all they know of me is fear.

My anger settled into the category of ‘spent storm.’ I found myself missing Karl. Not just then and there, but for all those years he’d been disappearing. The world lacks compassion. I didn’t have to remind him of that. A week or so before, he had passed me in the kitchen, hand held out in front of him, palm down. A spider was scurrying around on his skin, desperately seeking a place of refuge—a predator suddenly become prey; a man become a benevolent god. “I found him in my room,” Karl apologized, trundling open the sliding door and shaking his companion off onto the deck. “You’d have done the same,” he challenged, misinterpreting my smile.

I couldn’t have been prouder.

But it’s not enough, is it? Compassion?

“Of course not!” I shouted into the encompassing, uncomprehending wilderness.

Unimpressed, it shimmered in the heat, waiting for a voice that amounted to something more than the insignificant exhalation of an exasperated mortal. Unperturbed, the eternal forest went about its business, sucking life out of stones and soil, surging toward sentience through its patient eons—able to endure tortures because it was life without meaning, without suffering, without even the notion of an end.

“What’s expected of me?” I laughed because my question mocked me in the form of an imagined cartoon bubble materializing in the perfectly blue, omniscient sky. “So you’ve become a cartoonist now, have you?” I jibed at this latest incarnation of a God.

We cannot become saints until we’ve met the devil.

“Not now!” I groaned.

When?

I trudged on, as if the shuffle of my footsteps amounted to progress of some sort, past the evidence of human occupation: a graveyard, surrounded by a white picket fence; houses visible through the sparse, surrounding forest; a row of cabins in various states of modification or decay; abandoned vehicles; then solitude, with the occasional sign to let me know where there was, indeed, a crook in the road ahead.

“There is no devil,” I grumbled. “There’s only us.”

And evil?

“There’s only us,” I insisted.

And evil?

“Only us!” I yelled at the still-silent forest, crowding up to the verge of the road.

I settled into a steady gait after that, regretting my decision not to stay on the main road to Wells. The detour had only prolonged and intensified the uncertainty of my situation. What if Karl thought I’d gone missing because he couldn’t find me at the Barkerville visitors’ centre or the hotel? What if he went looking for me at the same time as I was looking for him? What a cock-up that would be! Just the kind of thing Noreen could be smug about. Her gloating wouldn’t be visible, of course. It would manifest as a kind of subtle, subcutaneous contempt, like the onset of influenza. An insinuating contagion suspired through her pores into mine, a toxic aura that would sour and sicken the two of us, the symptoms being a propensity to sneer and snarl.

“Stop it!” I checked myself.

I quickened my pace. Not quite to a run, but to a rate that forced my lungs to expand and contract more emphatically than I was accustomed to. Physical exertion always makes me aware of my body as a machine. When I dig in the garden, for instance, I see myself as a sort of excavator with a brain—the mechanics of hands, arms, and legs, swinging shovels of dirt into a barrow, somehow pneumatically driven. Our dog Zorro digs with gusto—that’s the difference; he gets his snout right in there and goes at it with berserk passion, at one with the act of flinging dirt out between his hind legs, barking into the cavities he creates in our yard as if he expects the world to answer. Zorro would have trotted up Reduction Road perfectly unaware of any demarcation between body and mind. His soul would not have recoiled into some corner of his nervous system from which he could contemplate his movements as those of a clumsily built robot, clattering and clanking down a back road, lost to any sense of equanimity or definable purpose.

There’s still four desolate kilometres to Wells from the point where Reduction Road reconnects with Route 26. If I’d been a practitioner of Zen, I would have breathed deeply, acknowledged I’d done the best I could to resolve my situation, and restored my sense of being to its calm and dignified unity. I’d have accepted the consequences of my actions and the world’s reaction with the same tranquility as a lake absorbing a tossed pebble, its underlying calm reasserting itself even as the unwonted ripples washed up on distant shores. Instead, panic intensified as I joggled up the road, my man-bag slapping my hip and sweat soaking through my shirt as profusely as if I’d just taken a hot shower with my clothes on. I couldn’t possibly make it all the way to the Wells Inn at the pace I was going, but couldn’t allow myself to slow down. All the while, I couldn’t help thinking that from ‘up there’—where it was surmised that a God lurked—I would look like a bug traversing a vast topography, who must inevitably run out of energy, out of life, and die. My progress would seem excruciatingly slow and laborious to such a being, who could arrive at any destination in a blink, because he—or she, or perhaps it—would of course be everywhere, forever, at the same instant.

“Piss off,” I huffed, angry that such an invention should be taunting me.

And at that precise moment, I heard the thrumming of an engine behind me, which I knew, without looking, must have been under the hood of a diesel pickup. I turned and stuck out my thumb, stumbling backward down the road.

Picked Up

“Thanks.”

The woman in the driver’s seat glanced up—she’d been gathering some papers and a backpack, clearing a space for me on the passenger side. “Hi,” she said. “Excuse my mess. Wasn’t expecting company.” The cadence of her rich, round voice penetrated like massage—it was the kind of voice ad firms use to lure people, the meaning of her words coming as an afterthought, an add-on to the texture of their sound. “Where you going?”

“Wells,” I said, resisting the urge to quip, ‘Crazy.’

“I can get you there.”

Hoisting myself into the cab, I pulled the door shut, swinging my satchel into my lap. She jammed the truck into gear and pulled away, accelerating aggressively and upshifting with instinctive competence. “Hope you don’t mind my saying, but you looked a bit… uhm… distraught.” She waited a couple of seconds, then added, “Like you were in a real hurry.”

She was looking straight ahead, but I could feel her sussing me out and couldn’t help looking her way. Athletic, mulatto profile. “My name’s Michelle,” she responded. “Not trying to stick my nose in, just wondering if I can be of help to a fellow traveller.” She smiled at that, as if she liked the idea and might enter it into a journal or something.

I sighed more deeply than I’d intended. “It’s my son,” I said, surprised at the swell of emotion that almost choked me. “He was supposed to pick me up at the Barkerville visitor’s centre; he didn’t show.”

“That out of character?”

“No,” I confessed. “He’s depressed. Me and my wife worry about him…

Sorry! I’m saying too much.”

We drove on in silence after that, Michelle downshifting, turning off at Pooley Street, then accelerating up the hill, the diesel growling fiercely. She pulled up at the Wells Inn. “Thanks,” I said, climbing down from the cab.

“I’ll wait here.”

“What?”

“If your son’s okay, let me know, and I’ll get out of your hair; if he’s not, or if you can’t make contact, you might need some assistance. Either way, the engine will be warmed up and ready to go.” She patted the dash. “Take your time. Me and the Beast aren’t in a big hurry.”

“Thanks,” I said, confused, grateful, and just a little suspicious.

Michelle smiled. “Have you checked the street?” she asked. Then, seeing my questioning look, added, “Your car. I’m assuming he was picking you up because he’d dropped you off, and that he must have been driving your car or a vehicle you’re sharing.”

“It’s not on the street,” I said, embarrassed that I hadn’t consciously ticked that box on my check list. I’d simply assumed… “I’ll look round the side of the hotel before I go in.”

Karl and I had adjoining rooms. By the time I arrived at his door, my sense of panic was building again. You get an idea into your head, and it balloons and morphs into all sorts of scenarios. All I needed was to hear Karl’s voice, and the demons would evaporate, leaving us with the stark reality we’d grown used to rather than any of their worrisome permutations. I rapped sharply. Waited. Rapped again. No answer. Scuttling back down the hall, I unlocked the door and entered my own room. A note had been slipped under the door: “Sorry, Dad,” it said. “I’ve gone on an adventure. Had to borrow the car. Karl.”

“Shit!” I said. “Shit, shit, shit, shit, shit!”

Free ride

“I’ll take you into Quesnel,” Michelle said. “You can get a signal there and try Karl on your mobile.” The Beast awakened and growled before I could offer a token objection, so I strapped myself in without protest, and we drove on: past the Deluxe Junk shop, down the hill, out of town onto Route 26, around the desolate shores of Jack of Clubs Lake and the Wells Refuse Site, then into a long stretch of dreary wilderness.

“What’s your son’s name?”

“Karl.”

Michelle looked thoughtful, as if the name Karl conveyed some kind of distinct meaning, the same way as ‘chair’ or ‘book’ or ‘or sledgehammer’ might. The Beast rolled on, taking the corners with a competent sense of traction and acceleration, then purring like a lion through the straight sections.

“Mind telling me a bit about him?” She kept her eyes forward while I looked enquiringly her way—as if she didn’t know the road like the back of her hand. “I’m a shrink,” she said after enough pavement had slipped by.

“Don’t get me wrong, but you don’t talk like one.”

She laughed. “Used to be a cop,” she said. “Sort of got tired of busting kids and decided I wanted to try fixing them instead.” We laughed. I knew it was a line she’d probably used a thousand times, but it was a good one, delivered fresh, and I liked her—really liked her. “Cashed in my RRSPs and went back to university. Best decision I ever made.”

“Sorry if all this is taking you out of your way,” I said. “But I appreciate what you’re doing.”

“My Mama used to say, ‘Never go out of your way, Midge; just make sure whatever direction you’re pointed is the way’.”

“Midge?” I queried, curious about how Michelle ended up being contracted into a variant of biting fly.

“Don’t ask me; ask my mama!”

“Mind if I call you Michelle?”

Midge glanced at me, grinned, then laughed. This time, a huge man-laugh that filled the cab, leaving no room for doubt. “You can call me whatever you want, Mister,” she said, slapping the wheel. “And I can pretty well assure you, I’ve been called worse.”

She liked me! Those clear, brown eyes of hers looked right into me and saw something to smile about, to admire, maybe even love in a daughterly way. Well, not daughterly, exactly, because I couldn’t imagine Midge as anyone’s daughter, really. Not in the typical sense of the word. I could see her in a pink dress at somebody’s birthday party, being schooled in proper etiquette, but even then, she would have been irrepressible, it seemed to me.

I couldn’t not love her.

“So?”

“Huh?”

“Karl. Tell me something about him.”

“Does this seat recline far enough to become a couch?”

“Stop putting me off. Tell me something about him.”

I told her the story of the spider on the back of his hand and how proud that made me feel.

Making Contact

West on Highway 26, left on 97 back into Quesnel, left onto St. Laurent Avenue, then parked—perhaps an hour out of Midge’s way. “I’ll leave you here,” she said. “When you’ve had your one-on-one with Karl, I’ll be in Granville’s coffee shop just round the corner. Take your time.”

She slammed the door before I could answer and strode off.

I switched on my mobile and watched it go through its launch sequence. There were a bunch of messages, one from Karl, one from Noreen. “Shit!” I grouched, skipping through to Karl’s: “Hi Dad. Guess you know I’ve taken off with your wheels. Sorry. I’ll understand if you sic the cops on me. I’m okay. My mobile’s on. I’ll be back in time to pick you up for the drive home, all right? I just got bored hanging around Wells. Couldn’t hack the thought of being there two more days.” There were traffic sounds in the background, mingling with Karl’s words, like he was in a city somewhere, walking… Vancouver? No, not possible. Quesnel?

My first instinct was to call him right away, but I checked the impulse. Noreen? Shouldn’t I get in touch with her first? I cringed, then skipped down to her message. “Hi hon, I hope you’re all right. Karl called and told me what’s going on. If you haven’t made contact yet, he’s okay. I guess you’re out of range or something. Call me…” then the audio menu cut in. “To replay this message, press 1; to leave a callback number you can be reached at…” I jabbed the big red ‘End’ button on my mobile’s screen hard, as if the action might actually, in some phenomenological sleight of mind, erase even the memory of the message.

Noreen hadn’t used that tone of voice since? I couldn’t remember when. She sounded concerned. For me! Which rankled “What the fuck is going on?” I punched in Karl’s number. “Hi,” his answering service chirped. “Karl’s not here. Leave a message, and he’ll get back at you when he’s around.” I waited for the beep. “Hi Karl. It’s Dad. I’m going to stay in Quesnel tonight, so I’ll be in range. I won’t leave town until I’ve heard from you, okay? I’m not mad, son—in any sense of the word. Just want to talk and make sure you’re okay. Love you.”

The message sounded phony—a desperate dad trying to sound chatty, not wanting to ramp up the tension and destabilize his weirdo son. Karl would see through that, of course, and understand. Surely he would understand?

There’s not much traffic on St. Laurent Street, human or vehicular. So a guy could sit slumped, thinking, in the passenger side of a parked pickup for quite a while without being noticed. You might even croak there and rest in peace for a day or two before someone called the cops—which suited me fine. After a couple of minutes, though, I remembered Midge and, with a twinge of guilt, hurriedly punched in Noreen’s number.

“Hi, Hon,” she answered. “You okay?”

“Aside from feeling like shit, yeah, I’m alright.”

“Did you get in touch with Karl?

“I left a message.”

“He’s okay. He called this morning and told me what was going on—sort of. I think he’s en route to Vancouver.”

“He left a note saying he was going on some kind of adventure? Scared the crap out of me.”

For a second, dead air. “He didn’t say anything about that to me, Kyle. Just that he didn’t want to hang around Wells for the next couple of days.”

“Did he say he was headed home?”

“No. I just assumed…”

“He said in his phone message that he’d be back in Wells to pick me up by check-out time. If he’s headed down to Vancouver, that means he’s going to have to turn around almost as soon as he gets there and drive straight back up here—it’s eight hours each way, more like ten if you stop for a coffee.”

More dead air. Get a grip, I admonished, wiping the accusatory tone from my voice. Okay, so she had forced Karl to accompany me to a place where we all knew he’d be bored stiff. So what?

“Sorry,” I said. “Not helpful.”

“It’s okay. We’re both upset.”

“Yeah, I know.” I paused, gritted my teeth and swallowed. “Look, someone’s waiting for me, so I’m going to have to ring off Noreen, but…”

“Who’s waiting for you?”

“I got a lift from Wells into Quesnel. I’m hoping I can rent a car here—if not tonight, I’ll have to book a room and rent something in the morning. Point is, if Karl is headed out to the coast, tell him not to worry about picking me up; I’ll make my own way back. If he’s in the general vicinity of Quesnel, then I’d like to ride back with him. If he gets in touch with you first, let him know that, please. Tell him to call me. I won’t leave Quesnel until we make contact.”

“Okay.”

“I love you. I know things have gone sideways for us, but I do love you.”

“I know. Bye,” Noreen answered, her voice gone flat.

The conversation left me feeling as deflated as a used airbag. I sagged in the seat for a moment, rallied, then shoved the door open and clambered out of Midge’s pickup. A slow drift of vertigo set in, as if I’d become overly sensitive to the ponderous spin of the world. “Midge,” I refocused, following her imagined scent around the corner, into Granville’s café.

She looked up from a book she’d been reading, The Confessions of St. Augustine. “Tormented soul,” she said, seeing my surprise. “But I suppose he did find a version of grace, if that’s what you’re looking for.”

“Why read him if it’s not what you’re looking for?”

She flipped the book shut and glanced at its cover—a bowed and bearded middle-aged man, robed in what appeared to be a blanket, with what might have been a crozier or staff resting on his shoulder. “I try to understand where people come from,” she said, shoving St. Augustine into her bag. “That man’s words still resonate in a lot of heads.” She gestured for me to join her at the window table. The light slanting in from outside emphasized her sharp, angular features and the strange beauty of her penetrating eyes. I forced myself into the opposite chair.

“So, what are you going to do?” she said.

“I’ve got to rent a room, for starters. Then tomorrow I’m going to have to rent a car.” Midge stared, uncompromising. “I didn’t get through to him. His phone sent me to voice mail, but Noreen—that’s my wife—said he connected with her. She thinks he’s en route to Vancouver.”

“But you’re not sure?”

I shook my head. “I’m not leaving Quesnel until I’ve talked to him. Noreen said he plans on picking me up Monday—that’s when my booking at the Wells Inn ends, and we were planning on heading home.”

“So where do you want to stay?” She looked amused when I shrugged like a lost dog. “I’ll make you a deal. My mobile cabin is parked just up the road.”

“Mobile cabin?”

“I hate calling it a trailer park home.”

We laughed, and for an instant, Midge’s smile was the only thing that mattered—that big, triumphant smile of hers. “There’s a sofa, if you want it.”

“But you hardly know me, Michelle.”

“I know you,” she said, “and I like you, and won’t bill by the hour for the couch… unless, perhaps, you want me to take you on as a certified nut case.”

There are moments you want the world to stop, when you want to freeze frame a feeling and make it last forever. I blinked, knowing she’d been thinking the same, sitting there in the window of Granville’s café.

The Errand

Do you remember how we first met?

Of course, dearest!

We could hardly call it a meeting, though. Could we?

Spirits seeing each other through each other’s’ eyes… even for an instant… there cannot be a meeting more meaningful, can there?

Madame Blavinsky had sent you on a mission, no?

Oh! She was such a deliciously devious creature, Madame was.

Tell him about it.

I’ll tell you, dearest, and he can listen in if he chooses. I don’t think he believes in me, which makes conversation awkward.

My eyes blinked open, but the paralysis of sleep numbed the muscles swaddling my bones. I could not move, not even if I’d wanted to raise my head from the pillow to look about Midge’s trailer. But I could hear the hum of the refrigerator, a dog barking somewhere off in the distance, the hush of leaves in the canopy overhead.

As you like, love.

You could hardly call it daytime when Madame and I awoke that morning. Everyone else in the house was sleeping still, but we were up, as was our wont. We’d made ourselves coffee and were seated opposite each other at the kitchen table. “I have something I’d like you to do for me today,” she said. “I’d like you to deliver a letter from me to that new priest at St. Saviour’s.”

“What’s the letter about?” I asked, for I’d never known Madame to be a religious sort. Spiritual, in a haphazard way, yes—a few candles burning on her bureau, occasional prayers to vaguely defined spirits that dwelt somewhere in the East, wind chimes, and such—but never religious in the proper sense. Certainly not in the hellfire and brimstone tradition of my father, nor in the ghostly ascetic mode of your mother.”

We needn’t bring Mother into this, my sweet, surely.

Why ever not? He knows all about your mother anyway. It’s not as if I’m opening the door and brushing aside the cobwebs in any of your darkest, secret closets.

As you wish.

Well, to be honest, I don’t wish. It was merely a passing reference, which you’ve raised to higher prominence through your objection. Had you simply let it pass, he probably wouldn’t even have made note of it.

That’s why I never became a politician, my dear. I must point things out—even little things—when they don’t seem right.

As it turned out, you might have made a better politician than a priest, my love. They laughed, and I sensed they might have touched cheeks in a perfunctory, loving way as a means of concluding their cajoling.

I had no idea where you lived and assumed Madame meant me to deliver her letter to the church, but she corrected me, prefacing her directions by remarking what an ‘unusual man’ she thought you to be.

Christopher guffawed, obviously entertained and somewhat flattered by the notion of eccentricity, when the accusation came from her. I strongly suspected the remark was meant for my hearing as much as his amusement, though.

She told me about your cabin, Christopher. And I must say, her description didn’t fill me with admiration for its new owner. “It’s not much more than a shack, really, on the road to Richfield, dearest,” Miss B. said. How she knew so much about you and your abode, I cannot say; what I do know, however, is that she must have made a point of finding out. By her description, I was certain she had been gathering intelligence for some purpose.”

Pooh! What reason could she possibly have had for spying on me? You’re just trying to make things more intriguing for our eavesdropping descendant here. I’m sure he’s got enough to take in without you adding fanciful twists to the story, eh?

She’d probably sent Cleaver around to snoop. I never looked, but I’m sure if I had, your name would have turned up in her diary. She was fascinated by you, you know.

They paused for a few seconds. Thoughtfully. Then Anna started up again.

As I was saying, I asked Madame what might be in a note a businesswoman such as herself was sending to a priest.

She waved me off. “You will know when the time comes; if the time comes.”

“Some kind of confession?” I persisted.

“Enough, now! You must go before the town is fully roused.”

With that, she shooed me from the kitchen, down the hall, and out the front door, leaving barely enough time for me to throw a cloak over my shoulders to keep off the morning chill. “You are beautiful, my dearest,” she soothed, running her hand over my cheek when I complained that I had not even had time to complete my morning toilette!

I hurried down Front Street, ignoring the glances of the few people who were up and about, clutching Madame’s letter in my left hand as if it were a passport granting free passage and might be demanded of me at any moment. The boardwalks ended, and I carried on through China Town, then beyond, into the pillaged wilderness of blackened sticks and stumps south of town, and farther yet, into a zone that hadn’t yet been ransacked for its ore. And there, I came across a simple wooden sign welcoming me to ‘The New Man’s Grove.’ I had to laugh.

Madame had described the place to me, and I’d heard others talk of it, too. None of that tainted or diminished my sense of… delight, I suppose… at your humble lodgings, my dear.

Don’t ask how, but I knew Christopher was blushing, and I sensed his coy-pride, even though he’d almost certainly heard Anna’s description of his wilderness manse a hundred times before.

I think ‘cabin’ might be too grand a word for the rough-hewn, wilderness shack you had bartered for, yet there was something pleasing about the place and the little clearing it occupied—a clearing sheltered by that fringe of forest, which had somehow survived the general desecration of the land all round. And the brook! What a joyful babble it added to the setting, ceaselessly talking, never stopping for an instant to listen. From the moment I stepped off the Cariboo Road and into that whispering, babbling copse, I felt at peace yet in conflict, if such a mood were possible, and the farther in I went, the more I felt a pampered intruder. Does that make sense, dearest?

If we were alone, I would concur with your every word, my love, but I feel it might sound maudlin in mixed company, so I shall let the echoes of my past affirmations speak for me on this occasion.

They laughed, and if I’d had mastery over the muscles that hoist lips into smiles, I would have joined in their delight; as it was, I felt frustrated and incapacitated—that I was incapable of anything but an intellectual grasp of their delight.

Do go on!

Daises, dandelions, fireweed, blue lupine—there were daubs of colour everywhere I looked, as if the wildflowers had been coaxed into this little clearing of yours, which still lay in the shade but would soon enough be touched by the late-summer sun.

The previous owner was entirely responsible for the state of the property… Christopher interjected.

Then he must have been a man like you, dearest, a man who appreciates every living thing, who draws life in from the surrounding forests and even up from the soil… Don’t object. We both know it’s true.

My inclination was to lean the note against your door and simply leave without disturbing you. But as I was stooping to do so, I thought, “No!” Why shouldn’t I place the note in your hand? So, I rapped firmly at the plank door and listened for signs of life within. It never occurred to me that you might have been sleeping or otherwise occupied, so I rapped again, more insistently, and when you did not answer my second summons, I peered in at the window.

Through the rippled glass, I could hardly make out anything in the interior gloom. But now I was determined to put the note inside if I could not actually place it in your hand. So, I lifted the wooden latch and entered your hermit’s cabin. The first thing that struck me as my eyes adjusted to the dark, was the tidiness. An ordered space equates to an ordered mind in my thinking, and I wondered if there was any room at all for spontaneity in your meticulous world. Every book was on its shelf, your bed was neatly made, the plank table wiped clean, and your kitchen, such as it was, fit for inspection.

But then my attention was drawn to a spray of wildflowers in a vase and next to that a medallion of stained glass in the upper pane of the window, which I hadn’t noticed looking in. It depicted what I took to be the Virgin Mary with child. On the opposite side of the window, a miniature painting of a perfect red rose, blossoming like a sacred stain on your rough-hewn wall.

“This,” I thought, “is a room open to visions.”

I was leaning the note against the vase on your table when you entered the cabin, and I froze in the act, looking at your figure, framed in the doorway.

“Hello!” you said, and I realized in an instant that there was absolutely no need for me to explain myself—that my being in your cabin was as natural an occurrence to you as the fireweed growing in the meadow outside, or the ceaseless chattering of your brook, or deer nibbling at the fringes of shrubbery surrounding your property. “I’m Reverend Newman,” you said, stepping forward with your hand outstretched in greeting.

Still, I couldn’t help feeling as if I’d been caught in the act of something untoward! That you should have been suspicious and should have asked some pointed questions, which I would have felt relieved to answer. So, after a few pleasantries, I explained I had been sent on my errand by Madame Blavinsky and that the note I had been placing on your table was from none other than her. Then I said my farewell.

“I do hope there is an invitation inside to visit Madame,” you said.

Our eyes had met already, of course, but there is a focus within focus that occurs when you are truly smitten, and in that instant I was overwhelmed by a passion I still have no words to describe. In that heartbeat, I knew completely the germ of everything I would ever be able to learn about you, Christopher Newman, and I virtually fled that knowledge, for I didn’t feel worthy of it.

And I was too stupid to perceive what had transpired between us, my love, too wrapped up in the theory of human passion to recognize the lightening flash for what it was—a burst that would permeate every corner of consciousness and inform all my dull philosophies with its brilliance.

Oh, for goodness sake, we should write an opera!

They laughed; I awakened.

Ignition

The phone buzzed on the coffee table like some species of mechanical insect stuck on its back. I grabbed it and accepted the call.

“Hi,” Karl said.

“How you doing?”

“I’m okay, Dad! You don’t have to worry, alright?”

“I’m your dad, son. It’s my job to worry.”

“And to feel proud, and confident, and happy, and all that shit.”

We laughed, the tension eased, like a Geiger counter moving out of a hot zone.

“Sorry ‘bout the car,” he said.

“We can talk about the car later, Karl. I’m just glad to hear your voice.” I paused, an incapacitating confluence of love and fear commingling into something like grief, tightening in my chest, making it difficult to speak.

“We love you son,” I croaked. “Your mother and I. That’s all that need be said. We love you and want to know you’re okay.”

“I’m okay,” he repeated. “And if you ask a third time, I’ll still be okay. Okay?”

“Okay!” I laughed. “I guess it’s my own state of mind that needs tending.”

“Where are you?” I asked when he didn’t bite.

“A little ways outside Prince Rupert. Slept in a rest area, but there was no signal there, so I couldn’t call, and I couldn’t reach you yesterday when I got to Quesnel, so I called Mum.”

“She thinks you’re headed to Vancouver, Karl.”

“Don’t know why she’d think that. I’ll set her straight this morning and let her know my whereabouts.”

“Good. She’s worried.”

“I’m going to sign off now, Dad. I just wanted to let you know everything’s alright. I’ll pick you up Monday, then we’ll be back on plan.”

“Meet me in Quesnel, son. I’ll have to drop off the rented car there anyway. There’s a coffee shop called Granville’s where we can rendezvous.”

“I know the place. See you there, Dad.”

Then he was gone.

Relief took hold, like morphine. Stupefied, I sat there, hunched, hands dangling between my knees for what might have been a full minute, wondering what I could do between the now and then of our situation. How could I prepare for what amounted to my reunion with Karl? Nothing came to me. I would call Noreen, of course, and compare notes. Which meant waiting until she’d had enough time to connect with Karl, too. Beyond that, nada, a void that could only be filled by him, being in the same space as me.

The door to Midge’s bedroom slid open. “Hi?” she said.

I smiled ruefully, aware that it was a piteous smile but not able to help it.

“I’m a light sleeper. The walls are thin.”

I nodded.

“Mind if I say something?”

She waited until I nodded again.

“You handled that well, Kyle. Lovingly, tenderly…”

“But?”

“You have to follow through.”

“What do you mean?”

“You said you could talk later about Karl’s decision to… uhm… take your wheels and leave you stranded. You need to follow through with that, not as a threat fulfilled but as an obligation between the two of you to work things out. Don’t let stuff like that go; use it as an opportunity to understand each other better.”

How could someone so excruciatingly beautiful be so wise? Someone who could almost be my daughter offer such sound advice? Midge read me like a book and smiled, making matters infinitely worse. She was wearing a T-shirt and pyjama bottoms, the cotton garments softening the contours of her wiry frame. Padding across the room, she stood before me for a second or two, exploring with her perfect brown eyes and taking me in.

Then she sat down beside me, the sofa cushions tilting in her direction. For a moment longer, we stared into each other’s eyes, then she stroked the nape of my neck with her slender fingers, eliciting a deep sigh from the very centre of me, almost a gasp.

“No commitments, okay?” she said.

I shook my head. “I can’t commit to that, Michelle.”

Her smile could have been meant for a child; it was a strangely grateful, pitying smile, which would have annoyed me coming from anyone but her. I reached up and did what I’d longed to from the moment we’d met—gently stroked her taught cheek with the very tips of my fingers, touching for the first time her smooth, dark skin. The tentative gestures of love accelerated after that, lips, hands, and tongues groping toward the inevitable, the necessary, something neither of us could avoid—the collision of love-making.

We awoke in Midge’s bed, in each other’s arms.

“I didn’t mean for that to happen,” she said.

“I couldn’t help it, Michelle, any more than I can escape the pull of gravity. I love you.”

“You have a wife and a son who’s got issues.”

“I love Noreen, but our marriage is beyond fixing. That’s got nothing to do with you and me. And I won’t just walk away from her; like you say, we have to ‘work things out.’ We’re not doing a very good job of it so far, but I think we can both read the signs.”

“And infidelity’s going to help with that? Make it less complicated?”

“Do you love me?”

Midge frowned, annoyed. Her body tensed against mine. I stroked her arm and shoulder, ran my fingers up the nape of her neck into her black, wiry hair. “It’s not that simple,” she sighed unhappily. “I’m not alone, either.”

I leaned away slightly to take her in, my brows arched in an exaggerated display of surprise. Midge had to smile.

“I have a daughter, Angela. Long story short, I’m a single, divorced mom, and she’s the centre of my world.”

Nodding, I held her close, and we lapsed into silence, letting this new knowledge settle between us, content for the time being with the uncertainty of our affairs.

“You know what gives me hope, Michelle?” She waited. “Neither of us has changed; there is no morning after that’s separate from the night before. We’re the same people we were when you stopped to pick me up yesterday. What I’m trying to say is, if you do love me, I’ll accept your love on any terms, but don’t ask me not to be your friend and, if we let ourselves give in to it, your lover.”

She drew me to her, and we kissed—a long, sensuous communion of lips and tongues that reignited the circuitry of our souls.

Loves me; loves me not

We couldn’t find a car rental place in Quesnel, so I hitched a ride with Midge up to Prince George, where she was headed en route to Prince Rupert, then by ferry to Port Hardy, and on to Strathcona Provincial Park west of Campbell River. “Buttle Lake,” she said. “It’s beautiful. You should go there sometime.” She’d mapped a detour that would take us to a car rental place in PG, where she could drop me off without having to park the beast and its tow.

“See yuh,” she said, as I gathered my things.

That’s how she wanted it. Curt. No concessions. No commitments. “I’ll call,” I promised, then shoved the door open and got out. I watched the beast lumber out of sight. No regrets, I told myself. No matter what, there would be no regrets or expectations. Only more desire and—perhaps, perhaps—a smidgen of hope, episodes of consummation.

But for now, she was gone; I had a car to rent; a meeting with Karl to rearrange (now that I’d be returning the car to PG instead of Quesnel); a call to Noreen that needed making; research to complete; a two-hour drive back to Barkerville.

I directed my steps toward the car rental office, where a young man greeted me from behind the counter.

Increasingly, it seemed, I was unconsciously appending that phrase ‘young man’ or ‘young woman’ to my descriptions of waiters, bank tellers, car rental clerks… The young man in the rental office went through his check list, asked politely the obligatory questions about insurance, provided details about rates and return procedures, and then directed me to Books & Company when I inquired about the nearest ‘funky coffee hangout.’ He’d smirked at my description of what I wanted, letting me know in not-so-subtle fashion that he’d pegged me as a retired boomer trying to resurrect his rebellious hippie consciousness.

“It’s up on Third, four or five blocks over.” He pointed in the general direction.

“Thanks.”

As we made our way across the lot to my set of rented wheels, I had to wonder if his stereotype fit, and then what Midge saw in me… And what she might see in the car rental clerk? He was intelligent, not unhandsome, fit, and—above all—young. Probably virile in ways I could hardly remember.

No commitments, I remembered. But the injunction rankled as I drove off the lot, following the rental guy’s directions. What did she mean? Had her love-making been a species of sympathy…

“Shut the fuck up!” I grumbled, angling the car into a spot across the street from Books & Company. A stuccoed box of cinderblock architecture circa the neo-brutalist 70s, it had been painted purple and given character by a cartoonish tromp-l’oeil wall of cracking plaster and urban decay. Perhaps a little overstated, I thought, but the motif suited my mood.

After ordering my latté, I chose a table close to the window. I wanted to be in a place penetrated by natural light but invisible from the street, a place where shadows had a lateral dimension and were cast by parallel rays that had traversed 93 million miles of vacuous space, not by the reworked light emitted by neon tubes fastened to a plastered ceiling. My desire for a sunlit table was moderated somewhat because I didn’t want to be seen by people walking by on the sidewalk. I wanted to be alone in an intimate, public space, not exposed to the instant judgments of every glancing tradesman, shambling derelict, or curious office worker.

Had to rent a car in PG. Meet me there at Books & Company Monday, 11 a.m., not in Quesnel. I texted Karl.

Made contact with Karl. He’s OK. Heading up to Prince Rupert. Will meet me in Prince George Monday AM, and we’ll drive down. I texted Noreen.

There, I thought. Done.

I prayed—in my existentialist mode—that neither of them would respond before I could get the hell out of mobile range.

The letter

Do you remember our second encounter, dearest?

Anna’s query, an almost coquettish challenge, caught me off guard. “No! Not now,” I pleaded. I had been reading the August 26, 1871, edition of the Cariboo Sentinel, downloaded from the UBC Historical Newspapers archive. I needed to refocus: zoom in on the past and put aside my awareness of Karl’s adjoining empty room; Midge at Buttle Lake, gazing at the same stars I could see out the hotel window; Noreen, scheming lord knew what back in Vancouver… What I didn’t need was another episode of my ancestors’ ghostly soap opera.

Of course! How could I forget? Christopher responded.

I sighed.

It was a week or so after I’d delivered Madame’s letter.

That got my attention.

They laughed, fully aware they were teasing their audience with their mysterious, reminiscing banter.

I knew by then what her missive was all about. Madame told me. Well, as you know, she couldn’t not tell me. After all, I was to be her representative, wasn’t I?

And I was looking forward to our next meeting, my love. Fervently!

Hmm? Judging by the company you were keeping, perhaps not as fervently as a future bride might have expected.

Christopher made to object, but she prattled on, obviously enjoying his feigned discomfiture.

Imagine our surprise when we spotted you at the Theatre Royal in the company of Miss Whitmore! Madame seemed amused. I wasn’t alarmed or jealous, of course. That would have been ridiculous! Just because I had been smitten at the first sight of you didn’t mean you had to put any constraints on your gadding about with the town’s school marm on your arm.

We were merely out for an evening’s entertainment.

Faugh!

I cannot deny there was an understanding between the two of us—you know that—but it was nothing that would bring dishonour on either party if we decided not to pursue our relationship. Had things gone farther, I would never have allowed myself to fall in love with another.

Such discipline! Such restraint!

Well, I must confess, my sweet, there would have been one exception. After meeting you, dearest—I mean truly meeting you and understanding what I felt for you—I’ve never had to exercise restraint; there’s simply never been another who could take your place. Snap! The trap had me by the leg, or the heart, or whatever part of my anatomy you wish to name.

They laughed, having forgotten me entirely, lost in their repartee. I imagined them looking fondly at one another, holding hands, perhaps hugging in that stiff, formal way apropos the 19th century.

So, what did you think of me in that precise moment at the Royal?

You know the answer, my dear. I thought I had a duty toward you, Madame, and the other girls in her establishment. To muddle that duty with anything … uhm… more personal would have been an abuse, a dereliction. My mind couldn’t comprehend the signs, dearest, so intent was I on my priestly responsibilities. I couldn’t see anything beyond that.

I was a project then; one of your good works?

Madam’s offer to install the stained glass at Saint Saviour’s was the project, dearest. I saw possibilities in that. The prospect of bringing a new light into the church, if you will. Working with Madam, even if behind the scenes anonymously, as she insisted, offered me a chance to build a relationship of trust, perhaps to change things for the better.

And me?

You were the only person in that theatre, really. I had to force myself to watch that silly play, to laugh at the right moments for Miss Whitmore’s sake, and to meld that vision of you back into the larger purpose at hand. It was all hopeless, of course, but I was too stupid to accept the reality of my situation. I was aware of you every second. But I thought I could will myself into obedience and could willfully transubstantiate love into infatuation. In retrospect, of course, I realize things had to turn out the way they did, but at that moment, I believed—truly believed—that my duty as a priest was to overrule the intense desires of my heart.

Transubstantiate!

A deliberate twist, my dear. A purposeful provocation.

What, exactly, had Madame written in her note?

You know what she wrote!”

Humour me, my love, for our friend, Mr. Welland’s sake.

I’m paraphrasing here, as you will know, but I can recite the gist of her letter…

‘Dear Reverend Newman,