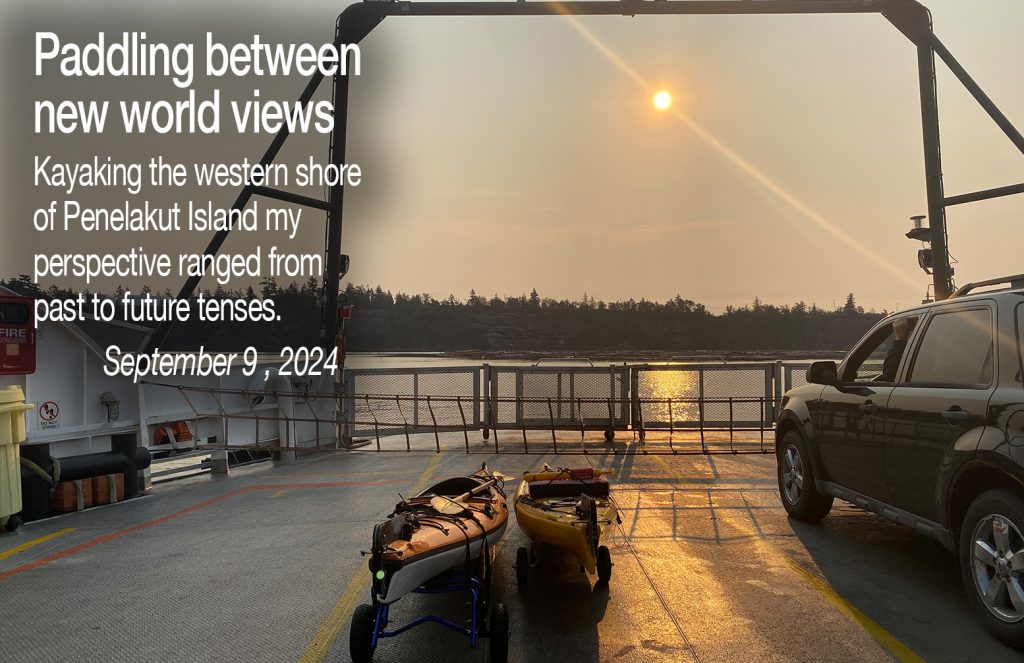

Paddling with my good friend Craig Harris yesterday down the western shore of Penelakut Island, I was haunted by an inkling of what it must have been like for a First Nations inhabitant, gliding through the same waters before the colonial era.

Much as I am enthralled by nature, I realized that I am but a tourist on the region’s land and sea; I can only imagine the deeper connection of a hunter-gatherer society, whose people ‘lived off the land’ and whose spiritual awareness was as deeply rooted and binding as that of the surrounding forests.

Before going any farther, an explanatory note: I am a Canadian of European ancestry. The influences that define me have been shaped and interpreted in that context and from that perspective. I do not want to be anything or anyone else. I do want to accept the challenges European social, scientific, and economic development and innovation have led to. The late-20th and 21st centuries have been a necessary time of reckoning. We either take responsibility for creating a better, more inclusive, more sustainable world, or accept the consequences and blame for our selfish, shortsighted decisions and behaviour.

It was from that perspective that I asked: What knowledge could we have gained from the indigenous peoples of North America and the world if only we had restrained our colonial incursions and taken time to learn from them what we had unlearned through centuries of abstracting technological and cultural development that had distanced us from the ‘natural world’?

That haunting question leapfrogged me into the present day, and a more timely consideration. What might we learn through the process of Truth and Reconciliation, as we honour the survivors of our colonial depredations and build a new relationship with them? That we are attempting such a feat makes me hopeful; if we can actually succeed, I will be truly proud as a Canadian of European ancestry.