[This is a Direct to Web story]

I try to avoid the thought, ‘This isn’t so bad.’ Because that might lead me to the admission that ‘it’s kind of nice’, which I’m sure would be misinterpreted. The procedure is meant to be purely clinical. An elderly man, in a sterile room, having patches of his body shaved so the receptors of a heart monitor can be glued to his sagging torso. My sentiments are strictly in the ‘like-being-around-young-people’ category, but the specifics of our situation, the semblance of intimacy, make me nervous.

The nurse’s hands move with a precision that suggests there’s no room for error here. Scrape, scrape, the plastic razor removes the short and curlies from five points of contact: two on my chest, three on my upper abdomen. Then she rubs the ointment on, peels the parchment from each of the receptor’s pads, and sticks them onto me, so they hang there like leeches.

It’s hard, under the circumstances, to keep the conspiracy theories from manifesting. ‘What exactly might they be listening to, through this harness that’s fastened to my skin?’ Those suspicions intensify when I realize the metaphor of ‘leeches’ doesn’t quite describe the species that will be clinging to me for the next 24 hours. They’re more like tentacles of a five legged octopus, whose neurones connect to a little black box the size of a mobile phone I’m to carry around with me as the creature sucks data out of my body.

‘What can you learn about a person by listening so intently and unremittingly to the beating of his heart,’ I wonder.

When she’s done with the techie stuff, the nurse shows me a ‘Patient Diary’, which she will later insert into a plastic zip-lock envelop that has the warning ‘BIOHAZARD’ emblazoned on it in both official languages. I’m to insert the scribble of my diurnal, minute-by-minute notes into a pouch on the outside of the envelop, the heart monitor and harness into the zip-locked compartment behind, then hand my pulsed record in to the ‘ambassador’ at the hospital entrance, who will make sure it finds its way to where it needs to go.

My record keeping must be curt. There are three columns to the diary: one to log the time, another to name my activities, and a third to list any symptoms I might experience. Activities might include ‘walking the dog’, symptoms things like ‘shortness of breath’.

The example are appropriate, I will discover. You really don’t know how boring your life is until you are asked to record the minutia of your days. If they’d cited an example like, say, ‘Wing Suit Flying!” or ‘Formula 1 Racing!’, I would have felt even more inadequate than I did before this bloody stroke added a knife-edge to my existence. ‘Shortness of breath’ wouldn’t even come close to describing the heart pounding rush of zooming through the alps at 200 kph, skimming over jagged granite teeth within centimetres of my life.

“Every decision entails risk.” I can hear Herbert pontificating over a pint of Dark Matter on the Sawmill’s patio. “You might get run over, deciding to cross the road,” he would say. Then add, in that nuanced, pain-in-the-ass mode of his, “Even in a crosswalk.” With Herbert repetition is sort of like the rivets and welds that hold a ship together. His logic has structure, you get exhausted just thinking about how you might dismantle the unassailable integrity of it.

“But happenstance doesn’t add zest to my risk-taking!” I want to shout at him. He’d have some kind of answer for that. I can see him smiling smugly, casually taking another sip of his beer, while I try to calculate the significance of a ‘mini-stroke’ on the future tense of my life’s story. “I didn’t decide to have a stroke!” I would complain.”So how can you call that ‘risk-taking?”

I know Herbert would have an irrefutable answer. One that would make perfect sense, even though it might be… would almost certainly be… perfectly wrong. That’s the thing I like most about Herbert, his ability to reason to wrong conclusions from almost any point of view. He’s like Socrates on steroids, his brain a network of unassailable algorithms that yield their own truth because they are based on false, hidden premises and mysterious assumptions. He makes me feel sane.

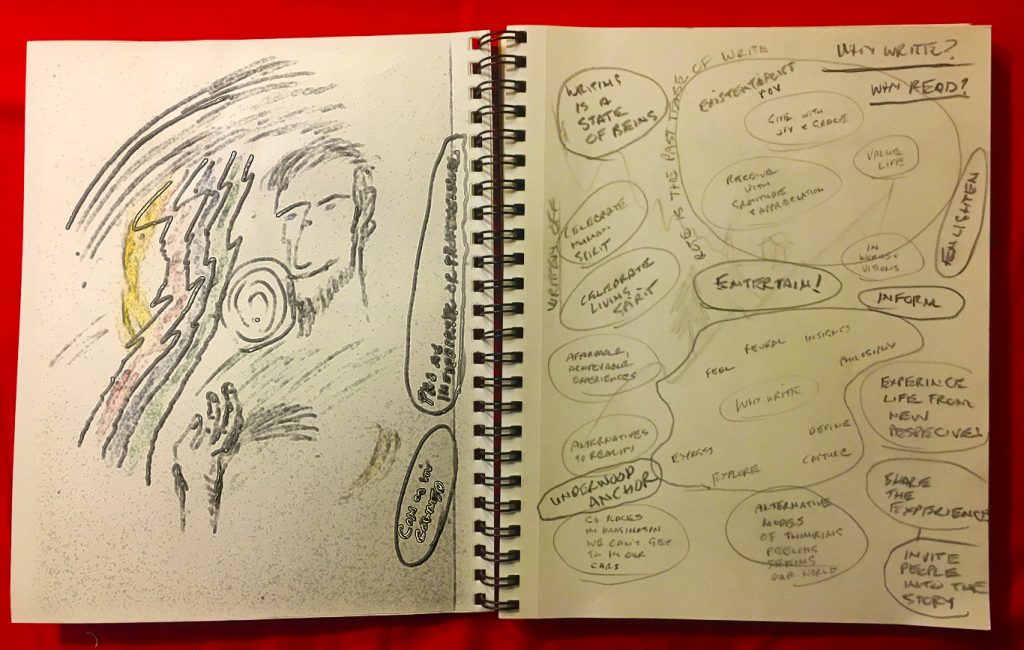

When I got home from the hospital, I made my first Patient Diary entry, aware of the octopus clinging to my flesh, monitoring my heartbeats as I struggled to enter the time. Everything I do with my right hand is a struggle now, especially writing. That’s how I knew something was wrong in the first place. Leanne asked me to write down an email address she was reciting during a phone call, and my hand couldn’t form the letters. They came out all shaky and crooked, sloping down the page like a five year old’s script.

What the fuck! No matter how hard I tried, I couldn’t get my hand and fingers to manipulate the pencil in a way that looked anything like normal. I pretended not to have heard her, left the room, threw the incriminating envelope into the garbage.

‘Drove home’ I scrawled under ‘Activity’; ‘3:20 PM’, under ‘Time’; I had nothing to report under ‘Symptoms’. I could have said ‘Depressed’, but that’s not the kind of information they were looking for. I could have added that it felt like my right arm was dying, that the weight of it tired me out if I insisted on actually using it. That, even if I let it hang limp from my shoulder like meat on a hook, just the sensation of its dead weight fatigued me. But there wasn’t room for that kind of descriptiveness in the symptoms column, so I left it blank.

Leanne got mad at me when I finally told her what had happened. After the chicken-scratch episode, I phoned my doctor’s office and was instructed to get my ass to a hospital and not to drive. I wanted to have some idea what was happening to me before I told Leanne, because she can’t stand uncertainty, has to fill in all the blanks and gaps with plausible explanations, followed up by the likely actions we need to take to deal with her scenarios. I’d have to stop my compulsive snacking, improve my posture, spend less time at the computer and watching TV, walk the dog vigorously twice a day, get rid of my belly fat and body flab… plus do what the doctors told me to.

She lectured me all the way from Chemainus to Duncan on our first trip to the hospital. Scolded about my slovenly habits and secretive attitudes. When she asked if I needed a drive to get the heart harness fitted, I said I’d be okay. “No need for you to sit around the hospital waiting for me,” I advised.

No matter how you slice it, the brain looks like a stalk of broccoli. I’d never seen my brain before, and if you showed me my CT and MRI scans, without any accompanying information, I wouldn’t recognize the folded cortex as my own. But it’s me all right. More me than the photos fading in our family albums, or imprinted in the circuitry of my friends’ mobile phones. Everything I know, or am capable of ever knowing or believing, is right there, in those pictures.

Everything!

Seeing images of my brain, collected by clunking, squawking, beeping, flashing machines, operated by technicians, who didn’t know me from Adam before I stepped into their clinical chambers, and would forget me almost before my moment of departure, confused me. It was like stepping into a house of mirrors…

No that’s not it. More like becoming an insect skittering about in my own neural network, able to see the inside of my own eyeball, then scurry up axions and hop synaptic gaps, until I burrowed my way into buzzing, vaulted chamber of my own brain and could sense the chaotic wonder of its electricity.

No! That’s not it either! It was as though I’d become an electron, aware of every other electron in the universe, and of the fact that I wasn’t an electron at all, but a something indefinable, an essence, a substance at the very core of living energy and matter, that could not be classified as either, or seen through the eyepiece of a microscope, or captured by the whirling cameras of a CT scanner.

If I wasn’t an atheist, I would have classified the experience of truly seeing my own brain as ‘religious’. And perhaps I’m not an atheist, after all, but a spiritual being who wonders, not at a god out there in a place called heaven, but at the ineffable miracle of every living moment.