Lucinda MacDonald

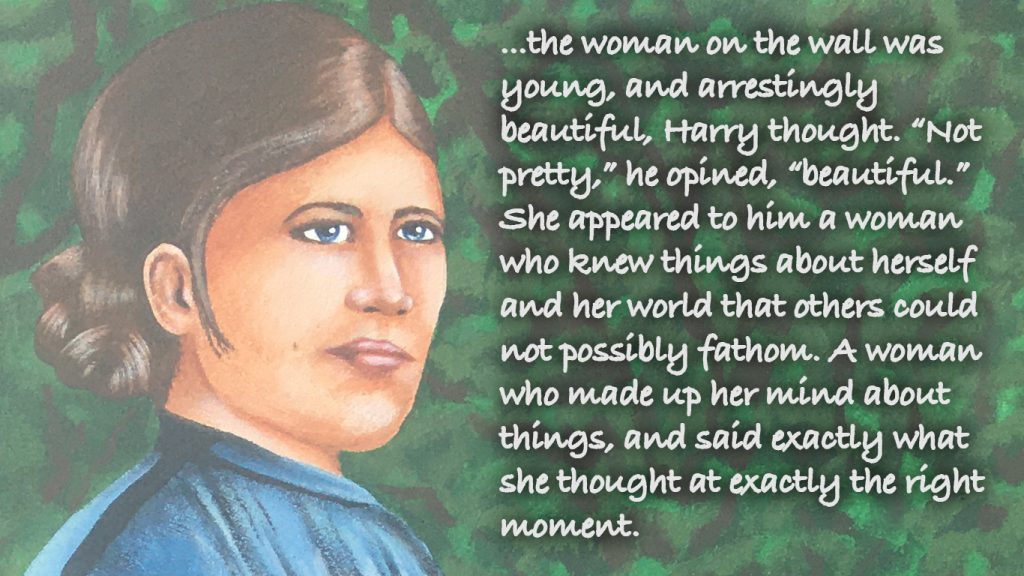

Lucinda MacDonald is a fictional character in my work-in-progress Entrapment. As a prelude to writing the novel, I am writing ‘journals,’ which timeline the life stories, thoughts, and actions of its main characters from their points of view. I am looking for commentators* and enactors* to gain a deeper appreciation and representation of Lucinda.

CAUTIONARY NOTE: This story will include depictions of physical, sexual and emotional abuse, violence and murder …

Craig Spence

Parts: 1-Meet Lucinda | 2-Tsunami | 3-Meant to Be

My name is Lucinda MacDonald.

I was born December 31, 1955, the first child of Carl and Miriam MacDonald. Father, whose only act deserving of that title was to fertilize Mother’s egg with his sperm, did not honour my birth with his presence. He was on a bender with some workmates that night and remained too hungover New Year’s Day to greet his newborn daughter until the afternoon of that momentous dawn.

He would remind me of that dereliction frequently once I was old enough to understand his course pronouncements and their full implications. If you didn’t know better, you might think he was trying to be funny, bringing up that embarrassing snippet of family lore…like, ‘Ha, ha, ha, only got to know you as afterbirth!’ Really, though, his words stung like a sandstorm, blinding me with impotent rage. My father liked being thought of that way. As a bastard. Me and my sisters and brother—Loretta, Louise, and Larry—learned to fear him before we learned to speak.

Children respond differently to intense, unremitting physical and mental abuse. From an early age, I presented as quick to anger and tough. By school age, I had endured five years of Father’s neglect, spiked with vitriol and abuse. I would instinctively shoot down anyone who earned the praise of our teachers, a reaction that narrowed the scope of my friendships. From kindergarten on I was seen as a sullen, snarly loner who attracted others with a gang mentality into her narrow circle of misfits—in short, a real bitch. I still struggle with that persona. It’s like an endless wrestling match inside the transparent womb of consciousness where the Lucinda I was brought up to be and the Lucinda I want to become do battle. Some days I’m better than others; then there are those days I’d rather poke you in the eye with a fork than listen to your inane blathering over breakfast. I can’t blame that contentious, cantankerous nature on Father alone; it’s embedded in my DNA.

Our middle sister, Loretta, turned out to be a fretting, nervous child, always ready to cringe at the approach of a stranger. Lucky for her, she was adorably cute and matured into a modest-verging-on-shy beauty. Any surviving seeds of decency that had not been exterminated in the contaminated soil of my father’s brain were activated by Loretta. There were actually moments when he forgave her and displayed symptoms of caring and affection. I wouldn’t go so far as to say he loved her. The man was incapable of loving; his starting point was hatred of everyone and everything, including himself. All I can say is he would have preferred Loretta for a wife than my poor, downtrodden mother—a fact that scared the crap out of me. It also spelled ‘DANGER’ for any would-be boyfriends prowling around, ‘wanting to piss on our gatepost.’ I can’t say I wasn’t jealous of Loretta’s looks and ‘sweet nature.’ I am proud that I overcame that nasty note in our relationship and loved her unconditionally… with the occasional lapse into snippiness.

Louise was the ‘smartypants’ of the family—the one who got told to shut up by everyone because she had to natter on and follow every tendril of evidence to its logical origins and inevitable conclusions. Father moderated his abuse when it was Louise’s turn because she amused him and he wanted to best her on her own turf. To resort to the belt or the back of a hand would have been tantamount to an admission of frustrated defeat he figured in his perverse calculous of family relations. He was often defeated. And despite her pain, outrage, and fear on those occasions, Louise was smug about it. There was also a hue of self-interest in his kid-glove treatment of Louise. Hitting her would be like smashing a valuable watch because it always insisted on telling not only the exact time but also how that minute, that very second fitted into the context of your universe. She was his ‘brain in a box,’ the one who might someday make our family fortune.

Then came Larry: Father’s greatest hope, and his most infuriating disappointment. I think Larry was nervous and wary by nature, but this tendency became more and more pronounced because he was constantly under Father’s malevolent eye. Larry was an artistic spirit and I’m pretty sure he’s gay—both capital crimes as far as Father was concerned. He also stuttered, which angered Father. He suspected ‘something was wrong with that boy,’ but couldn’t quite figure out what. Or perhaps he just couldn’t admit that any sperm spit out of his loins would turn out to be what Larry so obviously was: a sensitive child. Father wanted to hammer and twist him into shape—into what I can best describe as an entrepreneurial thug, a fascist, an oligarch. But you can’t build a phallic tower out of wood, canvas, and acrylic paint. You need steel, and concrete, and rivets, and an unyielding passion to crush anyone who gets in your way—above all else you need that… an inbred, ghoulish pleasure derived from pulverizing your ‘enemies.’

Larry could never turn out to be what Father wanted; Father could never let him become anything else—especially not the type of boyish man infused in Larry’s DNA. The outcome was predictable: Larry was damaged beyond repair, and Father suffered an embittering defeat at the hands of an ‘incurable wimp.’ Theirs was a tortuous evolution, painful to watch. Larry wanted desperately to please Father, but the gifts he had to offer were angrily, often violently, spurned. Of all us kids, Larry was Father’s only loyalist.

That he wasn’t the type of loyalist Father appreciated was all Mother’s fault. She ‘mollycoddled the boy’ and Father heaped more and more abuse on her because of Larry’s obvious failings. Mother was to blame—her, and the fact that Larry was in a nest with three ‘crinoline girls.’ We sisters were ruining Father’s one-and-only son. He hated us for that, and we hated him right back. He became especially enraged if Mother dared defend Larry.

I’ve left Mother till last. In a sense, she was always ‘last,’ hovering in the background of all our lives like a ghost—a vagrant spirit trapped inside the walls of our dysfunctional home. Father derided and punished her mercilessly, blaming her for everything: for his shitty job down at the docks; for having three girls in a row, then birthing a ‘nervous nelly of a son’; for his ‘crappy dinners’ and ‘dirty floors’; for the cost of living and all the ‘feminist bullshit’ he had to put up with… Each insult and slap added to the unsupportable burden that transformed her spirit into a lead ball where her heart should have been. She sagged, and staggered, and cowered, and finally became what his enraged torrents accused her of… a ‘deadweight, deadbeat burden,’ responsive as a punching bag to his taunts and torments.

He utterly destroyed her, which meant Mother no longer whetted his anger in any satisfying way; I was old enough to take her place. At 16, it became my job to clean house, cook dinners, do dishes, make sure my siblings were presentable and well-behaved, and so on. At first, he approached me with a faux display of sincerity and respect, as if I had graduated from childhood with honours. These counterfeit blandishments didn’t fool me or lessen my hatred; they only intensified my distrust. I knew what he was up to, but feared if I didn’t accept the responsibilities he was ‘offering’ life would become even more hellish for us all. So, angrily, I forced myself into my mother’s apron.

At first, Father continued his displays of gratitude and encouragement. I knew it was all for show—could almost hear the workings of his authoritarian brain clanking and grinding into place behind his leering mask. But I was shocked and surprised nonetheless when the fakery began to waver and fade, and the true nature of my surrogate motherhood role began to reveal itself. The demeaning perverseness of his malignant logic terrified me.

Not only was I expected to perform the household chores of a dutiful wife, I was also going to be forced to perform the filial nocturnal duties of a married woman. Honestly, it’s too sick to recount, but unless I describe this sordid passage, you won’t be able to fully appreciate the rest of my story.

“You are a woman now, Lucinda, and you shouldn’t be sleeping in a children’s room,” he pronounced one day. Until then we three girls had slept in one room, Larry had a room of his own. Now that I was ‘the mother of the house’ I took up lodgings in Larry’s room and he was shifted into the upper bunk that had been mine in the girls’ room. No one was happy with the arrangement. My sisters saw Larry as an intruder; Larry felt like one; I felt marked and vulnerable, and torn from my role as older, protective sister.

But it wasn’t until Father’s visitations began that I fully grasped the nature of my situation. Again, these unannounced intrusions were initiated as fraudulent pep talks and consolations. I can read faces as readily as a fortune teller can read your portended future in a hand of tarot cards and knew from the outset where his ministrations were heading. He would perch on the edge of my mattress, offering gruff but supposedly cheering assessments of the ‘little lady of the house.’ Inch by inch, he closed in. A squeeze of my shoulder, pat on my hip, peck of my cheek—I cringed and stiffened at the predatory insinuations of these gestures, not only because I knew what he was up to, but because I hated him irrevocably and fiercely and couldn’t stand the sight of him, let alone his touch. It was only a matter of time before these preliminaries would give way, and gentle coercion would morph into outright rape. I had no doubt my fate would be similar to my mother’s once that barrier had been crashed.

I should have slipped away while I had the chance, but couldn’t abandon my sisters and brother to the kind of vengeful retribution he would exact. Oh, I teetered on the edge. I knew what was coming. Should I cut and run? Endure his incremental degradations? Murder the lascivious bastard in his sleep? I had to come up with some kind of plan: I bought a switchblade and a can of bear spray, which I concealed under my pillow; and I stowed a backpack, stuffed with everything I’d need to survive on the streets for a while, under the back steps. My kit even included a bankroll, money I’d earned ‘borrowing twenties’ from ‘male members’ of the high school species for various sorts of ‘extracurricular’ activities…

Oh, I had a reputation at school. Was already known for what I would eventually become: Ms. Tough & Ready. I didn’t take shit from anyone—was force-fed enough of that at home—but I’d do favours. For cash. Up front. The boys love-hated me; I made sure they were afraid of me, too. I’d ‘borrow’ their money, then say, “You’ve already been paid,” if anyone dared ask for a refund. It was better than schlepping away at McDonald’s, I figured. Besides, I didn’t have time for an after-school job—unless I was giving a quickie hand job or blow job. There was Mom to be checked up on; chores to be done, and dinner to get on the stove before the old man clumped through the front door and flopped his weary carcass into his ‘favourite chair’ in front of the TV; then a sullen dinner to masticate before Father grabbed a beer and returned to his throne to watch more TV, or clomped out of the house to join his drinking buddies down at the neighbourhood tavern.

No matter what the hour, the denouement to every day was a bleary-eyed visitation. He’d slink into my room, and, as he shambled across the floor, I would do imaginary practice runs of my escape plan. I went over and over it, convincing myself it could work, and preparing for the worst if it didn’t. Either way, I wanted to confront him—have it out on my own terms, not his.

Miriam MacDonald

January 13, 1924 – November 10, 1976;

Beloved Mother & Wife

Father actually shed a tear at Mother’s funeral—the fucking crocodile. He moped and got drunker than usual for a few days after, but was back to his old self before the grass needed mowing over her grave. I was the one who found her, slumped sideways in his throne, mouth gaping, eyes clenched shut, as if she’d just witnessed something she couldn’t bear to look at, something particularly horrible in the waking nightmare that was her life. She died en route to hospital. ‘Beloved Mother & Wife.’ I could barely keep from yelling “Murderer!” at the snivelling prick, who had ordered that lie etched as a footnote onto the sparse declaration of her tombstone. My sisters, brother, and I mourned in sad silence; none of us could see her dying as anything but a release—her final breath collapsing her soul and her body like a squeezed accordion, the last moan wheezed out of her when no one was around to hear it. We wanted to love her, but there was nothing left of her to love by the time she passed; she had become a ghost, trapped inside a broken-down body

I didn’t suspect it at the time, but now believe Mother’s death set in motion the fateful train of events that were about to obliterate life as miserable and disgusting as we had known it. The tsunami didn’t reach our dilapidated front porch for some time. Father became terse and morose as if he no longer knew how to direct his chronic rage. I couldn’t figure what he was going through—what kind of metamorphosis was liquifying the guts inside his douchebag skin. Until he said to me, “How could she do this to me, the bitch? How could she?” He was tearing up, not with condolences for his dearly departed wife—that phase of his mourning was done with—but with rage. He glared at me, his reptilian eyes looking for something to focus on as if he was trying to catch sight of my very soul. And I knew in that moment my turn had come—that all his pent-up vengefulness was about to be unleashed, and that I would be the new live-in victim of his tortures.

When you’re confronted with a mad dog, the last thing you want to do is show your fear. I glared right back at him with unmasked hatred, and said out loud, “I’m not like her,” then stared him down, let him know I knew what he was thinking, and wouldn’t submit without a fight. I swear, his head expanded like a red balloon, his bulging eyes almost popped. I thought he was going to attack me then and there. But he looked away, banged the table with his fist, and growled, “Not like her? You’re all alike, you bitches!” Then he stumped out of the kitchen.

I had to get out of there. But when I passed by him on my way up the stairs to my room, he was scowling on his throne, boiling inside like a pot left on the stove with the element turned up high. His chair was strategically placed next to the front door and had a clear view down the hall that led to the dining room, kitchen, and back door. I thought of climbing out my bedroom window, but it was a sheer drop from the sill to a concrete sidewalk that ran down the side of the house. Shelter in place. It was my only option. I wedged a chair under the door handle. He’ll go ballistic, I thought. Good. I wanted to enrage him, for him to smash his way into my room and attack in a blind fury. I had my bear spray at the ready in one hand, my switchblade in the other, I’d either get out of there alive or go down screaming and slashing. I sat on the edge of my bed, at the ready

The dull thump of his footsteps coming up the stairs echoed my terrified heartbeat. My whole body clenched tight as a fist. I quelled the urge to rush across the room, remove the chair before he was checked by its resistance—an obstacle that would surely rile him. He’ll kill me, I thought. Bear spray and a switchblade? Really? I trembled. Had to force myself to sit up straight and look tough. Dangerous! You are dangerous. I pleaded, the silent despairing mantra of a prisoner doomed and damned. He paused at the door, I could sense his hand reaching for the knob, feel the heat of his anger. He was cocked like a hairtrigger gun. The knob twisted, the door rattled…

“Lucinda?” He sounded puzzled.

“Lucinda?” he repeated.

“Lucinda, open this door!” he demanded angry and afraid.

The door rattled again, more emphatically. Then he paused, just a second before crashing into it with his shoulder once, twice, a third time, which dislodged the chair, finging the door open, the hall light silhouetting him with its palid glare as he stood there, peering into the darkness.

“What are you doing,” he asked, unnerved by the scene his eyes were adjusting to. Trying to make sense of it.

That moment of uncertainty changed everything—unplugged the stopper of my rage and set a match to the incendiary bile gushing into me. Any sense of duty, fear, social obligation, or self-preservation shrivelled like ancient parchment in the inferno of my hatred and loathing. I wanted to kill him, lunge while he teetered on the threshold confused, and stab, stab, stab him.

But I checked the impetuous surge. He had to be the one who charged blindly into the vortex; I, the one who would stop him in his tracks, or die hissing, yowling, and clawing like a frenzied cat…

“What the fuck are you doing?” he yelled, then attacked.

Three paces, less than half-a-half-a-second, that was the space between us. He made for me, his arms reaching out to grab me by the hair, hands curled like the talons of an infuriated bird of prey. I held my ground, fixing him with a calculating stare, then, at the last milisecond, whipped out the bear spray and and hit him with a blinding shot of stinging acid. I ducked at the same time, rolling onto the floor as he toppled onto the bed bellowing like a mortally wounded dog. Scrambling to my feet, I turned to face him, knife raised, ready to strike.

Roaring and wailing, he flailed about trying to get a hold of me. I hit him with another shot of bear spray, just be sure, then backed away. He sensed my direction from the angle of the chemical stream hitting his face and the sound it made coming out of the cannister. “Fucking bitch! I’ll kill you!” He staggered toward me, arms waving, in front of him searching me out like the tentacles of a carnivorous insect. I slashed his hands; he howled again, shrinking from the lethal blade. Then, savagely, I plunged the knife into his side, yanked it out with a twist, then turned and fled.

Meant to Be

I’m going to fast forward a bit, because the day-to-day of becoming a successful sex trade entrepreneur isn’t the part of my story I want to dwell on here—maybe I’ll write a book about it someday, a deep throat, how-to edition about making money on a matress. But all you need to know for now is my bare bones backstory.

After a very precarious beginning on the streets, I developed a set of principles that have seen me through ever since. I’m pushing retirement age now, and I still have a date list of loyal clients who want to spend time with me. Shelve your puritanical notions about what it is to be a ‘sex trade worker’ (AKA, prostitute) before you draw your conclusions about me or anyone else in the biz. I don’t need your judgements or condolences! I run a practice that’s as useful and proper as any marriage counsellor’s. The fundamentals of success for me are simple. Number one: Avoid drugs, alcohol and the bar scene. I’ve seen too much to ever want to topple into that pit. Two: Run your practice as a business. Lucinda MacDonald Unlimited is my own business in every sense of the word. I’ll never be anyone’s ‘girl’ again, not even their call girl. Three: Work your way upscale. Setting out with a can of bear spray and my trusty switchblade in my purse, I moved off the streets, through agency and porn-poser jobs, into my own home business. I don’t need the implements or institutions of my trade anymore, but the blade I’ve kept as a momento—a horrific portent, as it turned out… But that’s a yet-to-come part of my tale in the telling.

My autobio would have had a very different middle and ending if it weren’t for the two most important people in my adult life: Josh Cruz, the recruiter and photographer who enticed me into The Muscle’s establishment; and our son—I use the adjective loosly—Manny.

I’d characterize Josh as a nice guy but, like a coat, he had to be either on someone’s back or a hanger to stand up straight. In other words, he had no spine. If he had of stood up to The Muscle when the time came, he’d still be alive. But he didn’t so he isn’t… end of story. He was a photographer and videographer, specializing in porn; a sometime recruiter for The Muscle, which was the calling card he used to draw me into the trade; and a common-law husband and father to me and Manny. Josh was a pretty apt choice of name by his deadbeat parents because joshing around was his stock in trade—his technique for sliding into and skating out of awkward situations and saving face when he had to surrender to other people’s will. He was funny, an attribute that made me and Manny happy most of the time, but pissed me off at crucial moments, when a live-in yuk, yuk comedian didn’t fit the bill. He was a good partner and father under the circumstances. I miss him, even though I’ll never forgive his fatal lapse.

Manny? Words can’t describe how beautiful he was—how prefect. Close your eyes and imagine an angel—as corny as that sounds. What do you see? Perfection, especially in human incarnations, is one of those words we can define but never comprehend. When I want to conjure up a perfect vision of him, I see Manny, smiling, laughing, teasing, dancing. I see his black, flowing hair; his intense blue eyes, reflecting me in him; his delicate hands, describing the shape of joy and philosophy in the space between us, or rhapsodizing on his keyboard or guitar in our cramped living space. But, like I said, perfection can only be defined—as soon as I try capturing his essence in words it eludes me, a ghostly image projected into mist. Our clumsy descriptions embarrass us. They expose our own inadequacy. Perfection, I’ve come to realize, is a state of mind. The only description of Manny’s perfection that works for me is ‘Love’—what it feels like to be utterly enthralled… Very few of us are capable of experiencing perfection.

Knowing that you will perhaps appreciate how my spirit writhed when Manny was taken away from me—how voraciously and insatiably I craved revenge! We bandy the word ‘hatred’ about: I hate spinnach, I hate this dress, I hate my ex and the bitch who stole him away from me, etc. But, like love, real hatred infuses every cell in your body. Except it’s a visceral rage. Disgust. And you can’t escape it. Even if you destroy the object of your hate, you will continue to hate its memory, and to wish it back into life so you can destroy it again, and again. It’s a poison that ignites your very soul and consumes you utterly. In its throes you are beyond the soothing and admonishing voices of reason. You come to hate anyone who counsels you to ‘calm down.’

Josh spotted me about six months after I took off. I couch surfed for a few days, until I found a job waitressing in a

To be continued

*Notes

20250205-0517 Lucinda finds a job as a dishwasher, then waitress in a James Bay restaurant (modelled on the Beacon Hill Drive-in). Starting at 16, she will work her way up into the manager’s position by the time she’s in her late twenties, then buy-in as an owner in her early thirties. It’s a family restaurant, and part of her story is the envy she feels watching normal families having fun outings. Happy kids, Happy Parents. She contrasts that with what she’s left behind, and—early on in her career—the danger her siblings still face. Her boss, the restaurant’s owner, Nick—becomes a fatherly figure for Ludinca. She likes him and comes to trust him. The feelings are mutual.

When she takes on the waitressing job she is boarding in a house on Cook Street. After a year, she feels confident enough to take on a secondary job of live-in building manager in a bachelors ‘penthouse’ suite in James Bay. The deal is ‘free rent’ in exchange for collecting other tenent’s cheques, approving return of deposits on vacated suites, showing prospective renters available suites, and monitoring cleaning and maintenance services.

Lucinda ‘retired’ as a prostitute after she intentionally became pregnant with Manny. She moved to a penthouse apartment suite in James Bay and took up a job as a waitress in a local cafe. She’d put aside enough money to supplement her income with investment earnings, and eventually started taking on select clients, usually older gentlemen who were lonely and craved companionship as much as sex. For this she charged flexible and modest rates, accompanying them to dinners, plays, movies and so on, then—on occasion—spending evenings with them at her apartment. Some of her clients were also frequenters of the restaurant where she worked—an arrangement condoned by her ‘boss. Manny spent nights with Josh when Lucinda had an evening or overnight client.

Commentator – A person with knowlege, especially direct experience, who can comment on the plausibity of characterizations and suggest possibilities I haven’t considered.

Enactor – Someone who would agree to pose or participate in photo enactments of scenes in the story, which could be used for design and pomotional purposes in the novel, publications, and social media.

Look for perfection in everything!

Perfection is sullied by mean spirits.

Perfecton is destroyed by greed and possessiveness.

Can I be a romantic, an idealist, and a realist at the same time?

We must constantly seek forgiveness for the necessities of living.

Cuts

So what’s the equation between ‘Nice Guy’ and ‘Perfect Son?’ Well, to start with, I have to refer to them both in the past tense. What do you do with a bookmark when you’ve read through to ‘The End?’ That’s become the torturing dilemma of my life.